Book Review: Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies

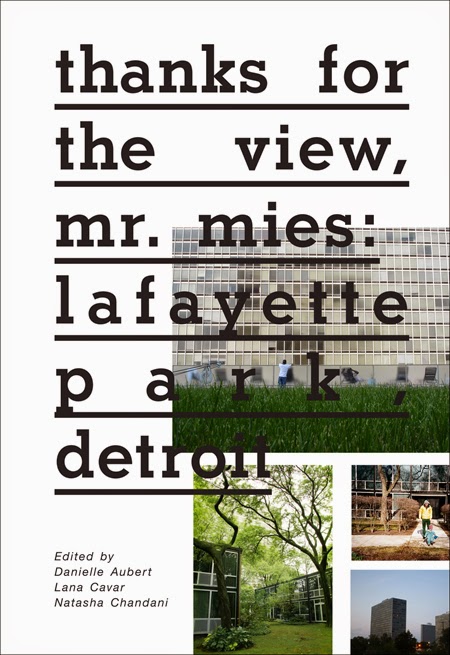

Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies: Lafayette Park, Detroit edited and with text by Danielle Aubert, Lana Cavar, Natasha Chandani | Placement, published by Metropolis Books, 2012. Paperback, 288 pages. (Amazon)

While I'm a big fan of book-length case studies on buildings, I'll admit that most tend to focus exclusively on architecture and process at the expense of social concerns, especially how a building is used after the architect is out of the picture. One book counter to this that comes to mind is Peter Friedl's Working at Copan, which features interviews with workers at Oscar Niemeyer's Edificio Copan in São Paulo, but I'm hard pressed to think of a book that makes the users the subject of a book. So Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies is a refreshing arrival this fall, not only for looking at architecture through the lens of Lafayette Park's residents, but for crafting a marvelous book that gives a full sense of the place through text and images.

Danielle Aubert, Lana Cavar and Natasha Chandani of Placement are the trio responsible for the book, what promises to be the first of a number of examinations of "the interaction of people and places...both specific sites (Lafayette Park, Detroit) and...types of locations (the beach, downtown, bus stops)." Their first place of study arises from the fact that each had spent varying amounts of time in Lafayette Park, a housing development near downtown Detroit designed by Mies van der Rohe with planning by Ludwig Hilberseimer and landscape design by Alfred Caldwell. Aubert has actually been a resident of two of three types of dwellings that make up Lafayette Park: a high-rise and a townhouse (the courthouse is the other type).

LP, as it's often referred to in the book by authors and residents alike, is comprised of three high-rise towers (1956-1963), fifteen two-story townhouse buildings, and four one-story courthouses (both types of low-rises are 1958-1960), all sitting on 78 acres. This physical make-up of the place helps to structure the book, which moves from a chapter on townhouses to one on neighborhoods, ending with the high-rises. This gives the book a progression from the ground-up, from the grass and the trees to the views across Detroit's urban fabric.

Through interviews with residents, essays by residents, tours, photo essays, archives and "LP Sporadics," the book is in essence what Phyllis Lambert accurately calls it: a field guide. The reader learns so much about the place, even though the longest block of text is probably about 1,500 words. It's the mix of voices, media, and topics that congeal to paint a very vivid picture of LP; site plans and floor plans don't arrive until the very end of the book, and understanding is not lacking because of this. A few of LP's traits that come across through different parts of the book are the stable nature of the neighborhood, especially when compared to the rest of Detroit; the appeal of the apartments, even though heating and cooling certain rooms in the towers can be a headache; the neighborliness that exists in the place; and of course those views.

The book gives voice to the residents, but it also illuminates one of Mies van der Rohe's lesser known projects. The book reveals that Mies, the mythical universal modernist, was also a humanist, crafting a housing project that is very livable and has sustained itself for decades. This may not be the point of the book, but ultimately an exploration of the relationship between people and place will hopefully serve to make the latter better. Architects should take note.

While I'm a big fan of book-length case studies on buildings, I'll admit that most tend to focus exclusively on architecture and process at the expense of social concerns, especially how a building is used after the architect is out of the picture. One book counter to this that comes to mind is Peter Friedl's Working at Copan, which features interviews with workers at Oscar Niemeyer's Edificio Copan in São Paulo, but I'm hard pressed to think of a book that makes the users the subject of a book. So Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies is a refreshing arrival this fall, not only for looking at architecture through the lens of Lafayette Park's residents, but for crafting a marvelous book that gives a full sense of the place through text and images.

Danielle Aubert, Lana Cavar and Natasha Chandani of Placement are the trio responsible for the book, what promises to be the first of a number of examinations of "the interaction of people and places...both specific sites (Lafayette Park, Detroit) and...types of locations (the beach, downtown, bus stops)." Their first place of study arises from the fact that each had spent varying amounts of time in Lafayette Park, a housing development near downtown Detroit designed by Mies van der Rohe with planning by Ludwig Hilberseimer and landscape design by Alfred Caldwell. Aubert has actually been a resident of two of three types of dwellings that make up Lafayette Park: a high-rise and a townhouse (the courthouse is the other type).

LP, as it's often referred to in the book by authors and residents alike, is comprised of three high-rise towers (1956-1963), fifteen two-story townhouse buildings, and four one-story courthouses (both types of low-rises are 1958-1960), all sitting on 78 acres. This physical make-up of the place helps to structure the book, which moves from a chapter on townhouses to one on neighborhoods, ending with the high-rises. This gives the book a progression from the ground-up, from the grass and the trees to the views across Detroit's urban fabric.

Through interviews with residents, essays by residents, tours, photo essays, archives and "LP Sporadics," the book is in essence what Phyllis Lambert accurately calls it: a field guide. The reader learns so much about the place, even though the longest block of text is probably about 1,500 words. It's the mix of voices, media, and topics that congeal to paint a very vivid picture of LP; site plans and floor plans don't arrive until the very end of the book, and understanding is not lacking because of this. A few of LP's traits that come across through different parts of the book are the stable nature of the neighborhood, especially when compared to the rest of Detroit; the appeal of the apartments, even though heating and cooling certain rooms in the towers can be a headache; the neighborliness that exists in the place; and of course those views.

The book gives voice to the residents, but it also illuminates one of Mies van der Rohe's lesser known projects. The book reveals that Mies, the mythical universal modernist, was also a humanist, crafting a housing project that is very livable and has sustained itself for decades. This may not be the point of the book, but ultimately an exploration of the relationship between people and place will hopefully serve to make the latter better. Architects should take note.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated for spam.