Palladio

Palladio

by James S. Ackerman

Penguin Books, 1976 (2nd edition)

Paperback | 5 x 7 inches | 196 pages | 96 illustrations | English | ISBN: 0140208453 | $6.95

BACK COVER DESCRIPTION:

BACK COVER:

by James S. Ackerman

Penguin Books, 1976 (2nd edition)

Paperback | 5 x 7 inches | 196 pages | 96 illustrations | English | ISBN: 0140208453 | $6.95

BACK COVER DESCRIPTION:

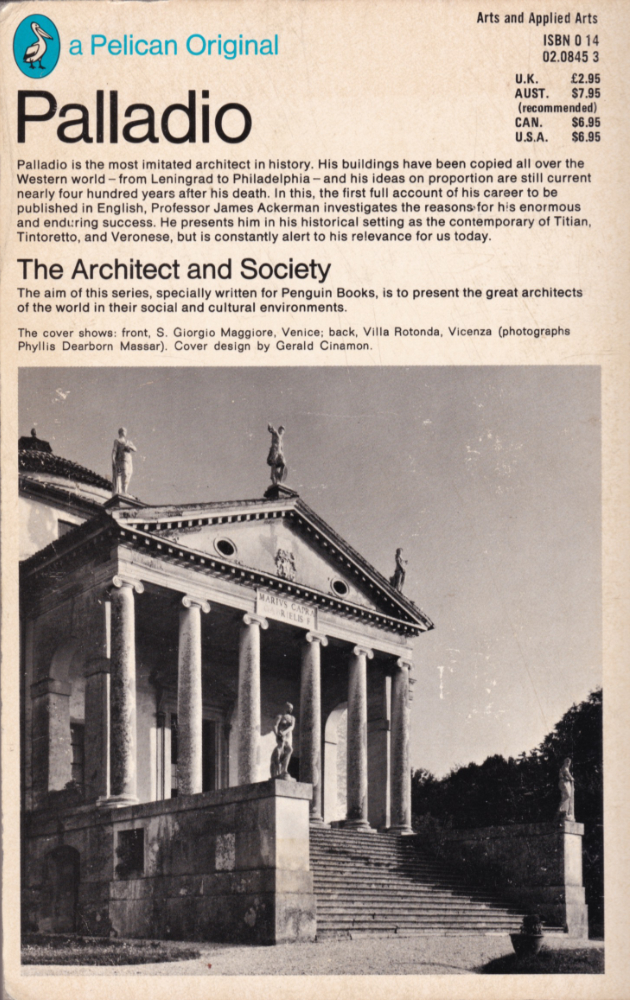

Palladio is the most imitated architect in history. His buildings have been copied all over the Western world – from Leningrad to Philadelphia – and his ideas on proportion are still current nearly four hundred years after his death. In this, the first full account of his career to be published in English, Professor James Ackerman investigates the reasons for his enormous and enduring success. He presents him in his historical setting but is constantly alert to his relevance for us today.

The Architect and Society – The aim of this series, specially written for Penguin Books, is to present the great architects of the world in their social and cultural environments.

James S. Ackerman was born in San Francisco in 1919 and studied at Yale and New York University. Professor Ackerman lived several years in Italy, beginning with service during [World War II], and [was] the author of many studies on Italian architecture, including The Architecture of Michelangelo (1961), which received the Morey and Hitchcock awards.

REFERRAL LINKS:

A couple of days ago, in my review of Barnabas Calder's Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency, I mentioned how that new book fits nicely into the lineage of architecture books bearing the Pelican imprint. A few years ago, before I shifted this blog to exclusively focus on architecture books, I took a look at some covers of architecture books put out by Pelican Books (an imprint of Penguin Books), which existed from 1937 to 1984 and then was relaunched in 2014. While Calder's book obviously fits into the second generation of Pelican, the first-generation titles included books by Peter Blake, Nikolaus Pevsner and John Summerson, among other familiar names, and such classics as Steen Eiler Rasmussen's London: The Unique City, Community and Privacy by Serge Chermayeff and Christopher Alexander, and Palladio by James S. Ackerman. The last was first published in 1966 in "The Architect and Society" series edited by John Fleming and Hugh Honour, the art historians who also updated Nikolaus Pevsner's Dictionary of Architecture.

Ackerman's Palladio is one of those famous books that many people know about but few people have read; or at least that's the way I see it as I'd never read it even though I've had a copy for a few years now. I think it was Ackerman's death in 2018 at the age of 97 that prompted me to get a copy; the abundance of its numerous editions means the small paperback is easy to find, cheaper now than its original cover price decades ago. Even so, it sat on my shelf, unread. Calder's atypical energy-focused history of architecture pushed me to read some parts of Palladio and feature it here. I can't help but agree with William Grimes's description of Ackerman's writing, in the New York Times obituary, as "limpid," clearly "arguing against the neoclassical view of Palladio as a cold logician." Although Ackerman details the proportions and dimensions of many a Palladio building in the book's concluding chapter, he concludes that "Palladio's inventiveness is more the point than his accuracy."

The last chapter, "Principles of Palladio's Architecture," comes after four chapters that present his life and buildings. "Palladio and His Times," the first chapter, is excellent for putting Palladio — born Andrea di Pietro della Gondola in 1508 (Count Giangiorgio Trissino, a mentor, give him the Palladio name) — into the context of Italy during the Renaissance, befitting the "architect and society" series. The three chapters that follow present the buildings he designed between 1540 and 1580 typologically: "Villas," "Civic and Domestic Architecture," and "Ecclesiastical Architecture." (The first of these chapters was expanded into a slim book titled Palladio's Villas.) Palladio had numerous masterpieces in all of these areas, so no wonder his influence on European and American architecture was so strong and lasting. Ackerman departs from a typical chronological presentation of the buildings in favor of a flowing narrative that accentuates the interrelationship of forms and ideas in Palladio's architecture. This book is an excellent introduction to Palladio, but one that could capably serve as the only book on Palladio in an architect's library.

BACK COVER: