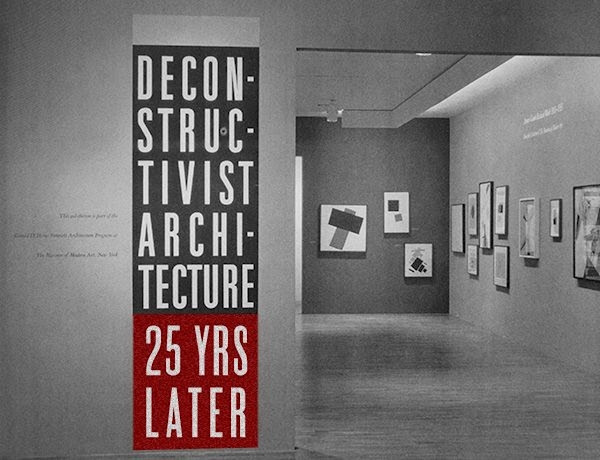

Deconstructivist Architecture, 25 Years Later

On the 25th anniversary of the exhibition, MoMA curator Barry Bergdoll hosted Deconsructivism: Retrospective Views and Actuality, "an informal conversation and reflection on the seminal show" with Eisenman, Tschumi, and Mark Wigley, who curated the show with Philip Johnson. This recent event prompted World-Architects to take a look back at Deconstructivist Architecure and trace the subsequent careers of the seven architects to examine the impact of the show and the changes in architecture in the last 25 years.

While it's hard now to find any common ground on the roles (if any) of deconstruction and Russian Constructivism played, it was generally agreed that the protagonists were battling postmodern architecture's eclectic historicism. Eisenman called the exhibition "a death knell for postmodernism," and Tschumi recalled that in the Parc de la Villette competition of 1982 he and Koolhaas (finalists in the competition) were not battling each other; they were battling Leon Krier, who embodied postmodern architecture. So while each of the seven architects had divergent theories and methods influencing their architectural projects, keeping with Johnson's emphasis on form, they embraced the chaotic, the incomplete, the fragmented, and the imbalanced.

What can also be generally agreed upon is that each architect has flourished in the ensuing decades, first getting buildings realized, then moving on to larger commissions as their offices grew and expanded overseas. The rest of this article runs through the seven architects in alphabetical order (brief bios can be found at right), looking at what they presented in the show, then what buildings they realized soon after the exhibition and most recently.

Coop Himmelb(l)au included three projects in the exhibition (Apartment Building, Vienna; Hamburg Skyline; Rooftop Remodeling, Vienna), one of which was completed that year. The Rooftop Remodeling is a conference room for a lawyer's office, perched upon a six-story building in the inner city of Vienna. The design juts beyond the parapet, like a parasite, an oft-used metaphor borrowed from Derrida, but one that did not influence Prix and Swiczinsky. Rather they refer to lines of energy "breaking the existing roof and thereby opening it," and describe their design as "a lighting bolt reversed and a space-creating taut arc." It is still striking three decades later, an illustration of the ability of small projects to have significance.

Five years after the exhibition Coop Himmelb(l)au realized the East Pavilion of the Groninger Museum, part of a larger museum complex designed by Italy's Studio Mendini. The 900-sm (9,680-sf) project is a good example of the duo's reliance upon intuition as practiced with blind sketches, drawings literally done with the eyes closed. The pavilion is not only a three-dimensional interpretation of the initial sketch via intermediate models, it makes their sketch a part of the facade in the black tar applied to the red steel plates.

Jump ahead to 2012 and the completion of the 58,000-sm (625,000-sf) Busan Cinema Center, home to the BIFF (Busan International Film Center). The subtle cantilevers of the Rooftop Remodeling and East Pavilion have given way to a soaring roof that covers a large urban space that includes an outdoor cinema. As will be seen with most of the other architects, increases in scale have been accompanied by increases in technology and engineering that allow daring forms, which in this case attempt to reshape public space for the 21st century.

At the time of the Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition Peter Eisenman was well established, due to his inclusion in the "New York Five" in the early 1970s, when he was also churning out one house design after another, each labeled with a Roman numeral. Only House II and House VI were realized, but those clearly show his belief in pure architectural form separate from site and function; famously, a reveal running through the middle of the bedroom in House VI made it impossible to furnish the room with a double bed. Eisenman put his competition entry for the Biocentrum in Frankfurt in the exhibition. The design recalls the grids of the House series, yet here they were manipulated through a series of steps based on the structure of DNA.

Eisenman's subsequent work also generated form through abstract operations, such as in the Aronoff Center for Design and Arts at the University of Cincinnati (now College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning). He layered and torqued various blocks and grids derived from the adjacent existing buildings he was squeezing the new design between. The pastels may have dated the building sooner than the university would have liked, but the interior's snaking atrium is where Eisenman's skillful manipulations pay off.

Similar operations and interior spaces are found in what promises to be Eisenman's magnum opus, the City of Culture of Galicia in Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain. Yet the ever-present grids are laid over curving landforms that unite the building strongly with its natural site. In effect, given the clearing required for the large project (partially realized and open to the public but currently on hold, per the architect during the informal conversation), the assemblage of buildings creates a new topography for the site, rather than making buildings as discrete objects.

Gehry completed his first European commission the year after the exhibition, a museum for the furniture company Vitra. The swirling design went well beyond the inexpensive materials and fragmented forms of his own house. The exterior can actually be seen as a manipulation of one of modern architecture's signature elements: whitewashed walls. The seeds of his later Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, Spain, can be sensed at Vitra, though the phenomenom the later work would become wasn't apparent at the time.

By the time his design for 8 Spruce Street in Lower Manhattan was realized in 2011, Frank Gehry had become the most famous living architect in the world; the building—made up of approximately 900 rental apartments across its 76 floors—was even rebranded as "New York by Gehry." The building and its rippling stainless steel facade are notable as an example of the consumer value of an architect's name (unthought of at this scale in 1988) and for revealing that tall buildings, normally the purview of conservative corporate firms, can be designed by one of the "Deconstructivist Seven."

Zaha Hadid burst onto the architectural scene in 1983 with her competition-winning design for The Peak, a leisure club inserted into what she describes as a "man made polished granite mountain" overlooking Hong Kong. If Hadid won the competition for the design—overlapping linear bars cantilevered from the mountain—or the remarkable paintings is now moot, for both skinny spaces and dynamic paintings remained defining characteristics of her architecture up to the exhibition and beyond.

Hadid's first major built work was completed five years afterDeconstructivist Architecture. The design for the fire station at Vitra's Weil am Rhein campus was generated by vectors that extended from the surrounding landscape, and layered concrete walls and a blade-like canopy gave the impression of frozen movement. The building is now used as display space for Vitra's chairs, since the redistricting of fire stations in the area made the station obsolete, not because of the rumors that the building's linear spaces could not fit fire trucks.

Since receiving the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2004, Hadid's output has boomed at a phenomenal pace. Per her website, at least 15 projects are currently under construction, ranging from a house in Moscow and a tower in Bucharest to numerous cultural institutions in the Middle East and Asia. She has designed three projects for China's SOHO developer, including the Galaxy Soho, which opened last November, and Wangjing Soho, which has been in the news because of a copycat development. Formally, Hadid has developed a recognizable style that is marked by grand, gestural curves, and spaces and surfaces that flow from one to another.

Three years after Rem Koolhaas co-founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in the middle of the 1970s, his "retroactive manifesto" Delirious New York was released. The book would cement the view of Koolhaas as an astute observer of the urban condition and an architect driven by research and analysis. His Rotterdam Building and Tower (aka Boompjes) was included in the exhibition, perhaps because of the way the slab was fragmented into smaller towers. The visual similarities of his study and Hadid's Peak is not a coincidence, as Koolhaas was a tutor of Hadid's at the Architectural Association in London, and she subsequently worked at OMA before starting her own office.

A subsequent publication that further defined the architecture of Koolhaas and OMA was the massive S,M,L,XL. The office had realized a few built projects by the start of the 1990s, such as the Kunsthal in Rotterdam, but those years focused on projects of increasing scale and complexity. The competition entries for the Très Grande Bibliothèque and Jussieu libraries in Paris, and the Zeebrugge Sea Terminal in Belgium, were especially ambitious projects in the "L" realm. Euralille in northern France made it clear how OMA's "XL" proposals respond to the myriad factors influencing the contemporary city.

If any project is indicative of Rem Koolhaas's occupations since the dawn of the millennium, it's the recently completed headquarters and studios for CCTV in Beijing. Koolhaas shifted his energies toward the East, researching places like the Po River Delta and winning the competition for CCTV with an anti-tower that exhibits his questioning of just about every convention.

Daniel Libeskind's project in the exhibition was the City Edge Competition for Berlin. He won the competition with a large angular bar that spanned blocks and streets; the city's reunification meant the project would only survive as drawings and models. Regardless, the importance of this project is undeniable: Its forms, angles, patterns, and cuts are formal themes that continue even to this day (pointed out by Wigley in an unflattering way during the panel discussion); even Libeskind's Milan office is called City Edge.

For Libeskind, the year 1988 also marked his winning the competition for the Jewish Museum in Berlin, a project that would get realized, though it would not officially open until 2001. The zig-zagging building with angular slot windows is oriented about a void that runs through the building. Pictured is one space that necessitates walking on metallic disks that reverberate throughout the space, turning the building into a vehicle for capturing the intangible aspects of the Holocaust. Some critics actually weighed in that the building was more successful when it sat empty for two years before opening, partly a testament to Libeskind's bare, abstract forms.

Libeskind has returned to the Jewish Museum to realize a glass courtyard and most recently an Academy across the street from the museum. But he has also been able to use his architectural language for developer projects, such as the huge Reflections at Keppel Bay in Singapore. Libeskind may have been pushed out of any direct involvement in the World Trade Center master plan, but in Singapore he has realized six undulating towers of various heights that gesture at each other on the skyline.

The year of the Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition also saw the opening of the first parts of Bernard Tschumi's design for Parc de la Villette in Paris. He won the competition in 1982, after a decade of "paper architecture" and manifestos, and as mentioned earlier it was seen as a victory over postmodern architecture. Along with Eisenman, Tschumi was most outspoken about incorporating ideas from the philosophy of deconstruction, evident in much of his writing about the park's layering of planes, lines, and points. The last are made up of the distinctive, "meaningless" red folies that received most of the attention.

The Parc de la Villette would not be completed in full until 1998, and in the decade between the exhibition and its completion Tschumi realized a number of projects. The first was the Glass Video Gallery in Groningen, Netherlands, a small pavilion that now bears his name. The glass walls, structure, and canted floor question notions of stability and security, but Tschumi attests that the building was his first project to deal with the concept of the envelope. Given his emphasis on event and action in projects like his influentialManhattan Transcripts, the relationship between envelope and experience was the key part of the concept.

Such considerations extend to the recently completed first phase of the Alésia Museum and Archaeological Park in France. The circular building is wrapped in a patterned wood veil that sits in front of glass walls to affect one's view of the surrounding landscape, the site of the Battle of Alésia. When considered relative to the other six architects in formal terms, Tschumi's architecture is the most diverse, refusing to bear the architect's signature.

So what is to be made of the Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition, the participating architects, and the state of architecture 25 years later? It's impossible to deny the success of the seven architects since the 1988 show, and the exhibition probably paid a large role in that—it's impossible to tell otherwise. What has happened with their success is that the institutions, developers, and other clients that previously built in the postmodern style commissioned these architects to design their museums, towers, and so forth. This take prioritizes form and style over other considerations, but Deconstructivist Architecture did just that, helping to make the fragmented forms on display digestible to a wider audience. The show may have been up for only two months, but like the International Styleshow in 1932, its impact extended well beyond that tenure.

Wigley asked a question during the panel discussion (video is above, for those who couldn't make it to the sold-out event) that gets at the state of architecture in the near future: "Could an exhibition similar to Deconstructivist Architecture happen today?" Does today's architectural climate invite a genre-defining moment? Tschumi asserted that there is nothing today to battle, like postmodern architecture 25 years ago, but then he offered that a show now would be called "Iconism," addressing the obsessions of architects to make icons. With many of the today's icons designed by architects from the exhibition, this means that the battle will be against what Tschumi and his fellow protagonists have accomplished in the last few decades. So on the 25th anniversary of the Deconstructivist Architecture show, the panel has ironically provided its own death knell, inviting a younger generation to step up with alternatives.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated for spam.