Unless

Unless: The Seagram Building Construction Ecology

Kiel Moe

Actar Publishers, March 2021

Hardcover | 7 x 9-1/4 inches | 300 pages | English | ISBN: 9781948765398 | $34.95

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

REFERRAL LINKS:

Kiel Moe

Actar Publishers, March 2021

Hardcover | 7 x 9-1/4 inches | 300 pages | English | ISBN: 9781948765398 | $34.95

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

This book presents a terrestrial description of the Seagram Building. It aims to describe how humans and nature interact with the thin crust of the planet. Architecture reorganizes nature and society in particular ways that today demand overt attention and new methods of description.

The immense material, energy and labor involved in building require a fresh interpretation that better situates the ecological and social potential of design. Architecture and society would benefit from alternative descriptions of building and architecture as terrestrial activities that help imagine how to maximize the impact of architecture on its environment. I argue that the enhancement of a particular building should be inextricable from the enhancement of its world-system and construction ecology. A “beautiful” building engendered through the vulgarity of uneven exchanges and processes of underdevelopment is no longer a tenable conceit in such a framework. Design can and should evince the inherent solidarity and reciprocity of people, places and politics involved in building architecture. The environmental and social conditions of this century suggest a much more recursive description of architecture and the terrestrial processes that converge through building. To this end, the book mixes construction ecology, material geography, and world-systems analysis through architecture to help articulate all the terrestrial activities that engender building generally and, more specifically, through the example of a most modern of modern architectures: the Seagram Building. The book evokes a broad range of evidence to help explicate the terrestrial activity of this architecture to make design far less abstract and much more literal. Unless architects begin to describe buildings as terrestrial events and artifacts, architects will—to our collective and professional peril—continue to operate outside the key environmental dynamics and key political processes of this century.

Kiel Moe is a practicing architect and the Gerald Sheff Chair in Architecture at McGill University. ... He has published ten books on architecture including Empire, State & Building; Wood Urbanism: From the Molecular to the Territorial; Insulating Modernism: Isolated and Non-Isolated Thermodynamics in Architecture; Convergence: An Architectural Agenda for Energy; and Thermally Active Surfaces in Architecture.

REFERRAL LINKS:

Kiel Moe's Unless: The Seagram Building Construction Ecology treads familiar territory to his earlier Empire, State & Building, which examines the long history of the building site where the Empire State Building is located. Unless ventures just over a mile north, to Park Avenue and 53rd Street, to take a deep dive into the "terrestrial architecture" of the Seagram Building, the modern masterpiece from 1958 designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson. The story of the Seagram Building's creation has already been documented in extreme detail, but Moe uses the iconic building to explore the broader "uneven and asymmetrical exchanges" that occur in the production of modern architecture. The particularities of the building and its main architect, who was known for a "less is more" approach, allow numerous contradictions and unexpected details to bubble to the surface.

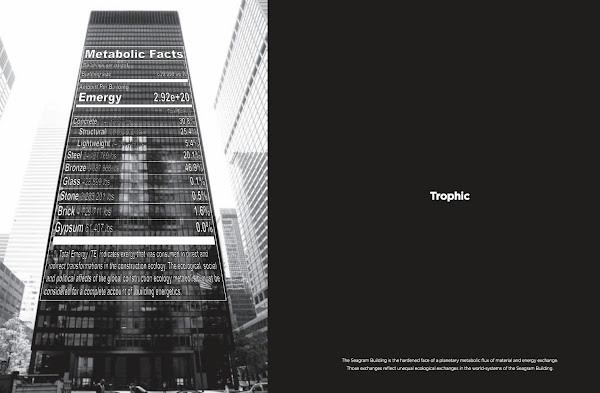

The highly visual book starts with a series of spreads (six of them are below) that touch upon some of these uneven exchanges and also lay out for the reader the structure of the chapters that follow. This "trophy" building is seen on one page but then immediately followed by a photograph of "a house crushed by tailings in the company town adjacent to the Chiquicamata Copper mine, where copper for the Seagram Building's brass facade was extracted." When considered together, these images of two products — one intended through architecture, the other an outcome of exploitive practices — make it hard to look at the glass and steel tower long celebrated for its innovation and minimalism in the same apolitical way. The photos in these early spreads reappear later in the book, with the copper mine found in a lengthy chapter on the building's famous facade, titled "Dies, Dyes & Dies." The chapter explores the dies that cast the brass profiles, the dyes that give it the appearance of bronze, and the distant deaths that were the inadvertent outcome of building the building. If "God is in the details," as Mies is quoted as saying, the devil is there as well, in the deaths at the hands of capital-A architecture.

Unless arrives at a time of great reckoning in social, economical, political, and ecological realms. Moe is focused primarily on the last, though clearly they are all related, intertwined in the "uneven and asymmetrical exchanges" that have long prevailed in modern architecture. Therefore, architects cannot continue with apolitical positions in which the effects of architecture are externalized. He wrote a book describing the "terrestrial architecture" of a well-known piece of architecture "so that our understanding of the past can change, and so the future of architecture can start to change as well." Elsewhere, Moe asserts that "architecture has entered an age of fundamentally altered states and more contingent realities," such that "claims of autonomy and autarky of architecture" cannot continue. Climate change is the strongest argument for architecture to recognize its impact and to strive, in Moe's words, to maximize "its impact on the environmental and society in positive and mutually-reinforcing ways." Ideally the lessons Unless offers would affect the future of all buildings, not just the minority of them lumped into "architecture."

The position of Unless outlined above and in the book's early visual spreads is not particularly new (if anything, it's strongly in line with much architectural criticism today), but the means of exploring architecture's role in global flows of materials and energy is rich and rewarding. This isn't to say it's an easy read; although it is abundantly illustrated — many of the pages feature diagrams pulled from an exhaustive digital model of all the materials in the Seagram Building — the text is often unnecessarily abstruse, which I also lamented with Empire, State & Building. Moe is clear and vivid in historical accounts that carefully describe, for example, the Seagram Building's relationship with copper mining, but thankfully such descriptions outnumber the portions geared to people who can differentiate between energy, anergy, exergy, and emergy. That said, the book's strong position on architecture's role in the 21st-century production of buildings outweighs any difficulties in comprehending the technical aspects of Seagram's terrestrial architecture. Although it's an important book arriving at the right moment, I hope in his next book Moe applies the same approach to a building that truly embodies the "positive and mutually-reinforcing" future he sees for architecture.