The Work

The Work: Architecture, Urban Design, Drawings and Sculptures

by Rob Krier

Birkhäuser, August 2021

Hardcover (2 volumes) | 10 x 12 inches | 1,344 pages (The Work I: 712 pages; The Work II: 632 pages) | 3,000 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9783035622799 | €128

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

REFERRAL LINKS:

SPREADS:

by Rob Krier

Birkhäuser, August 2021

Hardcover (2 volumes) | 10 x 12 inches | 1,344 pages (The Work I: 712 pages; The Work II: 632 pages) | 3,000 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9783035622799 | €128

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

As an architect, urban planner and sculptor, Rob Krier has created a multifaceted oeuvre which is presented here in a comprehensive manner for the first time. After graduating, Krier first worked with O. M. Ungers and Frei Otto before setting up his own studios in Vienna and Berlin. He later taught at the Vienna University of Technology from 1976 to 1998 and as a visiting professor at Yale University in 1986. Drawing on a wealth of historical models and archetypal patterns, he developed new typologies of streets and public squares as an architect and urban planner, and was responsible for numerous urban development projects throughout Europe. These included the perimeter block development on Ritterstrasse for the IBA in Berlin, the residential complex on Breitenfurter Strasse in Vienna, the Kirchsteigfeld district in Potsdam, and numerous projects in the Netherlands.

Rob Krier, architect, former professor at the Technical University Vienna (1976-1998).

REFERRAL LINKS:

Hearing the name Rob Krier, I immediately think of the book Urban Space, the 1979 English edition of Stadtraum in Theorie und Praxis, published in 1975. That influential book is actually all I think of, since I've never followed the career of the architect and urban planner born in Luxembourg in 1938. The book is indicative of Krier's neo-traditional take on buildings and cities, with carefully composed facades defining urban spaces that are formed rather than leftover. It is one of 100 seminal books I included in Buildings in Print, regardless of the fact its influence is strongest on New Urbanism, a movement I'm more critical of than praiseworthy. The subtitle of the new two-volume monograph summarizing Rob Krier's career spells out the two realms of his architecture and urban design, but it also includes drawings that suitably describe unbuilt projects, plus sculptures, which have been a nearly lifelong passion of Krier's and are an unexpected addition to any architectural monograph.

The two volumes of The Work offer chronological presentations of Krier's output, the first from 1955 to 1999 and the second from 2000 to 2016. For some reason, the table of contents in the second volume includes the project dates but the first volume does not, the latter of which is less than helpful in such a large book. Another editorial misstep is found early in the first book, in Kenneth Frampton's lengthy essay, "Krier in Context." His words are accompanied by a few dozen illustrations of projects by Krier, as well as by others who influenced the architect, but none of the illustrations are keyed to mentions of the projects in the text. The images are labeled with figure numbers, not project names, but those numbers are not carried through to the text — linking words and images is made unnecessarily hard, regardless of proximity. This frustration doesn't last though, since the architecture, urban design, drawings, and sculptures that follow are presented in a straightforward manner, with symmetrical page layouts and honest accounts by Krier throughout.

Urban Space appears on page 107 in The Work I, in a text called "Farewell to Stuttgart: New Beginnings in Vienna, 1975–1976." More than half of the 1975 book is devoted to urban plans for Stuttgart, both Krier's schemes and those of his students at the University of Stuttgart. Following three years at that school, Krier up and left to teach at the Vienna Institute of Technology, at the same time opening an office in Vienna that he would retain until 1994. "Just as my friends had predicted," he admits in the "New Beginnings" essay, before the reader encounters the projects spanning those nearly two decades, "I only accomplished a small number of projects in Vienna." Such statements are indicative of Krier's frustration permeating the book, be it over the wider contemporary architectural culture, the disappointing outcomes of some built projects, or situations that kept projects on the drafting table and even derailed his life's work.

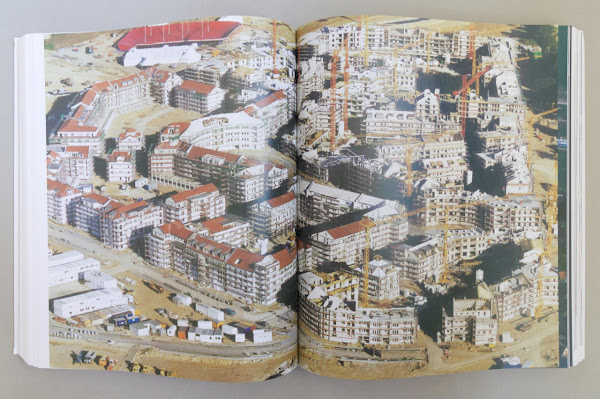

Near the end of his Viennese tenure, Krier opened two offices: one in Montpellier, France, in partnership with Nicolas Lebunetel; and one in Berlin with Christoph Kohl. The latter partnership realized Kirchsteigfeld, the masterplan for a new town for around 10,000 inhabitants in Potsdam, Germany. The project's presentation, shown partly in the spreads below, comes in the middle of the first volume, following primarily unbuilt projects documented through Krier's distinctive drawings. Eighty pages of photographs, drawings, and text describe Kirchsteigfeld, what must have been a watershed project, one that even incorporated some of Krier's large figural sculptures. Throughout the book, images of Krier's sculptures are inserted between the projects, suitably in chronological order but bearing no apparent relationship to the projects other than generally "belonging to one family," in his words. That disconnect is not the case at Kirchsteigfeld and other projects where enlightened clients were open to the insertion of artworks on buildings by Krier or the other architects hired to design individual buildings.

The project that follows Kirchsteigfeld is another important masterplan: Brandevoort, a residential district for some 20,000 residents in Helmond, Netherlands. The project also had a client who incorporated Krier's sculptures into the neighborhood, but what comes across most prominently is the Dutch style of the elevations facing the streets and squares. Krier discusses in the book how working in a new place involved researching the character of local buildings in order to create continuity — the antithesis of modern urban planning, as he espoused in Urban Space. This neo-traditional approach endeared clients to him, especially those in the Netherlands, as expressed by the many Dutch projects that follow Brandevoort across both books.

Flipping forward to The Work II, a couple of projects stand out as particularly important. First is a large residential block in Bilbao, Spain, that Krier worked on with Nada and Marc Breitman; the trio worked on the earlier, unsuccessful competition for Ijburg in Amsterdam, reuniting in 2005 for a project close to the Guggenheim Bilbao. Here Krier's sculptures serve as caryatids, appearing to prop up projecting bays and standing freely across the facades. Second is Cité Judiciaire in Luxembourg, an urban district that started in 1991 and therefore seems out of place in the second of the two chronological volumes. The placement must be intentional, though, since its completion date of 2008 coincides with the great recession and the end of Krier's architectural practice. With all ongoing projects stopped, Krier threw himself into his sculptures, since that time making them during the summers in a workshop in Andora, Italy, and devoting winters in Berlin to "meditatively" review his "activity in the form of books," none as comprehensive as The Works.

SPREADS: