The Layman's Guide to Classical Architecture

The Layman's Guide to Classical Architecture

by Quinlan Terry, edited by Clive Aslet

Bokförlaget Stolpe, March 2022

Hardcover | 8-3/4 x 10-3/4 inches | 250 pages | 220 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9789189069817 | $38

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

A discussion that stands out to me in the four chapters on the five Orders (he puts Corinthian and Composite together in one chapter) is the author's detailed analysis of modillions. Found mainly in Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite Orders, modillions are projections on the underside of the cornice that often alternate with recessed coffers. The spacing of the modillions has to relate to the column below it as well as to any changes of direction of the cornice, which can be seen most dramatically in the drawing and photograph below depicting Terry's design for Baker Street, London, in 1998. Later in the book, in a chapter on Baroque architecture, the author sketches a church in Rome that features modillions and coffers that are "correct" in elevation but not in plan, pointing out what the architect (Carlo Rainaldi) could have done to make it more successful. Within his commentary is the unwritten assertion that the success of Classical architecture is dependent upon a detail as small as modillions and how they fit into the arrangement and articulation of other elements, each one depending on the other and therefore fitting into a whole — ideally a correct and pleasing whole. Unfortunately, this attention to detail does not extend to the labeling of the drawings in the book, where arrows and dotted lines in red get lost atop the sketches and — especially — the linotypes, making them unnecessarily hard to read.

Near the end of the book are two chapters that address the relevance of Classical architecture more than 2,100 years after the Pantheon was built in Rome: "Appropriate Materials and Construction for Buildings that Will Endure for Centuries" and "Classical Architecture as the Hallmark of its Time and Place." With climate change and sustainability being tantamount concerns now — especially in regard to the embodied energy and carbon in existing buildings — I find myself agreeing with the former: cheap, "disposable" buildings that cannot be recycled should not be built. But should buildings that last centuries be Classical? Must they be Classical? I have a hard time saying yes to those questions, since modern and contemporary architecture is full of examples of buildings that depart from Classicism but take a similar approach in terms of a smaller scale and load-bearing construction and materials. (Think Kahn, Wang Shu, Zumthor, etc.) If modillions express the good of Classical architecture, for Terry the expansion joint embodies the bad of modern architecture. Eliminating expansion joints, though far from likely, would force all architects to create buildings less reliant on unsustainable materials and assemblies. But "green" equalling Classical is open to debate — one I'm guessing Terry would be up for.

by Quinlan Terry, edited by Clive Aslet

Bokförlaget Stolpe, March 2022

Hardcover | 8-3/4 x 10-3/4 inches | 250 pages | 220 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9789189069817 | $38

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

In this beautiful illustrated survey, British architect Quinlan Terry (born 1937) presents his ultimate guide to classical architecture. With intricate and lively sketches, he explains the classical orders of architecture that were created by Vitruvius around 100 AD. The tradition of building using these orders was maintained well into the 20th century, until modernism began to dominate architecture. With this book, Terry, a strong proponent of classical architecture, aims to place focus on the kind of architecture that dominated the field for almost 2,000 years in the West—the vocabulary and heritage of which is known by few today. The book contains a large number of Terry’s drawings and sketches from travels, as well as linocuts. Also included are his drawings of such quintessential examples of the use of classical orders as St. Mark’s Square and San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice and Inigo Jones’ St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, alongside drawings of Terry’s own structures, such as Brentwood Cathedral in Essex, England. In addition, Terry compares his own studies with those of Andrea Palladio and Vincenzo Scamozzi.

Prince Charles, another advocate for classical architecture, who holds Quinlan Terry as his favorite among contemporary architects, provides the preface.

REFERRAL LINKS:

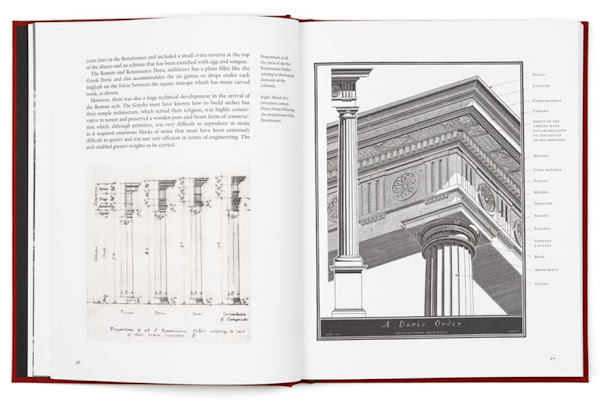

Although I agree with the saying "you can't judge a book by its cover," I've found that with architecture books the covers say a lot about what's inside. In the case of this book written by British architect Quinlan Terry, the cover indicates that Classical architecture will be explained to laypeople — ideally clients — through drawings, and those drawings will look at the Orders and elements of Classical architecture in a vantage point looking upward. Such a perspective departs from plan and elevation drawings favored by architects like Andrea Palladio who wrote treatises to Classical architecture, pattern books that were studied by architects and students of architecture. Terry's guide for people without such an education makes Classical architecture that much understandable, by putting people in front of Classical buildings — many designed by Terry himself — and having them virtually crane their necks upwards.

The spreads shown here capture how such upward-facing sketches and linotypes span the book's twelve chapters, which move from detailed explanations of the five orders to arguments for the preference of Classical architecture over modern architecture and its relevance in the time of climate change. Moving from the study of proportions and Classical elements to a way of building that could save the world is a bit of a long walk, but it's an enjoyable one nevertheless, thanks to Terry's fairly casual writing style and his reliance on drawings, which appear to take up more of the book's pages than the text. Therein lies Terry's motives for writing a book for laypeople: more clients demanding Classical architecture are needed for traditional building and design to supplant modern architecture this century. He writes on page 193: "When I started working with Raymond Erith there were about two or three other serious Classical architects practicing, but now there are probably over fifty in England and many more in America. The credit for this goes not to the architects but to many laymen who request that their new house or offices should look similar to buildings they admire from previous centuries."A discussion that stands out to me in the four chapters on the five Orders (he puts Corinthian and Composite together in one chapter) is the author's detailed analysis of modillions. Found mainly in Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite Orders, modillions are projections on the underside of the cornice that often alternate with recessed coffers. The spacing of the modillions has to relate to the column below it as well as to any changes of direction of the cornice, which can be seen most dramatically in the drawing and photograph below depicting Terry's design for Baker Street, London, in 1998. Later in the book, in a chapter on Baroque architecture, the author sketches a church in Rome that features modillions and coffers that are "correct" in elevation but not in plan, pointing out what the architect (Carlo Rainaldi) could have done to make it more successful. Within his commentary is the unwritten assertion that the success of Classical architecture is dependent upon a detail as small as modillions and how they fit into the arrangement and articulation of other elements, each one depending on the other and therefore fitting into a whole — ideally a correct and pleasing whole. Unfortunately, this attention to detail does not extend to the labeling of the drawings in the book, where arrows and dotted lines in red get lost atop the sketches and — especially — the linotypes, making them unnecessarily hard to read.

Near the end of the book are two chapters that address the relevance of Classical architecture more than 2,100 years after the Pantheon was built in Rome: "Appropriate Materials and Construction for Buildings that Will Endure for Centuries" and "Classical Architecture as the Hallmark of its Time and Place." With climate change and sustainability being tantamount concerns now — especially in regard to the embodied energy and carbon in existing buildings — I find myself agreeing with the former: cheap, "disposable" buildings that cannot be recycled should not be built. But should buildings that last centuries be Classical? Must they be Classical? I have a hard time saying yes to those questions, since modern and contemporary architecture is full of examples of buildings that depart from Classicism but take a similar approach in terms of a smaller scale and load-bearing construction and materials. (Think Kahn, Wang Shu, Zumthor, etc.) If modillions express the good of Classical architecture, for Terry the expansion joint embodies the bad of modern architecture. Eliminating expansion joints, though far from likely, would force all architects to create buildings less reliant on unsustainable materials and assemblies. But "green" equalling Classical is open to debate — one I'm guessing Terry would be up for.

FOR FURTHER READING:

- The Four Books of Architecture by Andrea Palladio (Dover Publications, 1965)

- The Classical Language of Architecture by John Summerson (The MIT Press, 1966)

- Classical Architecture: Rule and Invention by Thomas Gordon Smith (Gibbs Smith, 1988)

- New Classicism: Omnibus Volume edited by Andreas Papadakis and Harriet Watson (Academy Editions, 1990)

- Architects Anonymous by Quinlan Terry (Academy Editions, 1994)

- The Elements of Classical Architecture edited by Henry Hope Reed (W. W. Norton, 2001)

- Classical Architecture: An Introduction to Its Vocabulary and Essentials, with a Select Glossary of Terms by James Stevens Curl (W. W. Norton, 2003)

- Sketchbooks: Collected Measured Drawings and Architectural Sketches by George Saumarez Smith (Triglyph Books, 2021)