Three Lessons from Three Monographs

Writing a blog devoted to architecture books means featuring monographs — lots of monographs. Not exclusively, of course; but before this blog transitioned to its current weekly format, one of the thematic days of the week was appropriately devoted to monographs: Monograph Monday. Monographs are an unavoidable part of architecture books. No matter how often they are decried as passé, endangered, or even dead, monographs persevere as one of the best means of presenting a firm's built and unbuilt works and for marketing the same to new clients. These "uses" of monographs find their origins in books on Frank Lloyd Wright but were most influential in Le Corbusier's Oeuvre Complete, put out in eight volumes between 1929 and 1970, the last one posthumously. Though edited by others, the series of monographs were strongly controlled by Le Corbusier, which enabled a comprehensiveness many contemporary monographs forget about in their photo-heavy presentations. These three monographs don't necessarily follow the Corbusian model (Richard Neutra and James Stirling did that, strictly so, decades ago), but they do build upon it in ways that led me to think they should be commended and emulated — in bits and pieces, at the very least — by other architects.

Before delving into the three monographs, here is a trio of statements I derived from considering the Corbusian lineage and from examining the most beneficial traits of these three books; while these do not come from, nor apply to, each of the three monographs, their intertwining nature means architects/monographs following one statement may just as readily be following the others:

- Monographs should be comprehensive if not complete, presenting numerous built works and unbuilt projects instead of just focusing on a few select buildings. Not every building by an architect is a masterpiece (those should get their own book-length case studies, also), but neither do masterpieces exist in a vacuum; they are part of a larger body of work that overlap and influence each other.

- Monographs should convey the voice of the architect, if not in the literal words of the architect (admit it, many architects are not good writers, nor should they be expected to be great writers), in order to get across what makes them unique and worthy of a monograph (not all architects are worthy of monographs, furthermore).

- Monographs should function as archives, providing information (images, text) that goes beyond what is presented on an architect's website and incorporating other materials of interest (articles published elsewhere, for instance), so they are valuable for researchers and scholars, now and in the future.

The three monographs:

- Caruso St John Collected Works: Volume 1 1990–2005, published by MACK, 2022 (Amazon)

- Juha Leiviskä 2000–2022 edited by Elina Standertskjöld, published by Museum of Finnish Architecture, 2022 (Buy at Museum of Finnish Architecture website)

- Shigeru Ban: Timber in Architecture edited by Laura Britton and Vittorio Lovato, published by Rizzoli, 2022 (Amazon / Bookshop)

|

| Spread from Caruso St John Collected Works: Volume 1 1990–2005, courtesy of MACK |

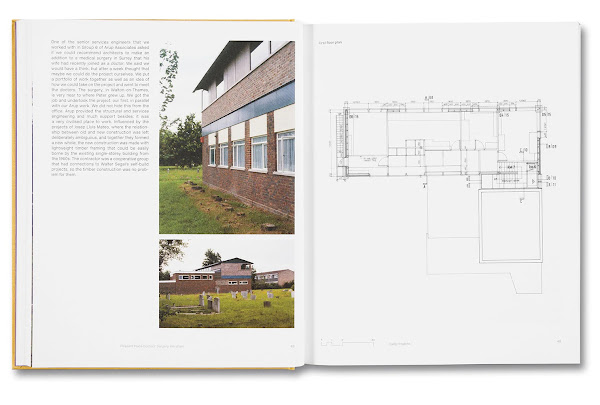

If one of these three monographs conveys all three of the statements/qualities described above, it is the first volume of Caruso St John Architects' Collected Works, part of the first batch of architecture books released last year by MACK, a UK publisher previously focused on art books. From its simple linen cover with drawing of the steel facade of their Swan Yard project, strong stitching, and matte paper selection, to its documentation of built and unbuilt works over the title's fifteen years and the incorporation of articles and interviews previously published in Quaderns and other venues, the book is a beautiful object that is rewarding and refreshing on every turn of the page. By opting for an approach that is "collected" rather than "complete," the architects — Adam Caruso and Peter St John — were free to depart from a chronological presentation of projects or one based on thematic chapters, as many marketing-driven monographs do; they opted for an organization that is fluid, with chapters grouping projects by era ("Early Projects"), type ("Exhibition Design"), or interests ("Poetic Realism," "Lewerentz"). The resulting mix, where projects and previously published texts are given equal weight — as evidenced in the table of contents, above — is the monograph's strongest feature, capturing the practical and intellectual concerns of the duo.

|

| Spread from Caruso St John Collected Works: Volume 1 1990–2005, courtesy of MACK |

Like numerous other architects, my first exposure to the work of Caruso St John was New Art Gallery Walsall, completed in Walsall, England, in 2000, shortlisted for an EU Mies Award the following year, and also a finalist for the RIBA Stirling Prize. The building is documented at length in the "Contemporary Art" chapter, first in an essay by Rowan Moore (from an eponymous book on the gallery published by Batsford in 2002) accompanied by photographs, and then in numerous pages of drawings and additional photographs. While the drawings are also presented, generously enough, on the Caruso St John website, the inclusion of Moore's lengthy essay is indicative of how the first volume of their Collected Works goes beyond the website and incorporates content from a myriad of sources. Flipping through the book feels a bit like rummaging the architect's own archive, while at the same time having arm's-length access to a library with relevant books and journals. The design of the book, from its cover and type of paper to page layouts and selection of fonts, captures the minimal yet rich and sensual ethos of Caruso St John Architects' buildings.

|

| Spread from Juha Leiviskä 2000–2022, courtesy of bookm-ark.fi |

The name of the Museum of Finnish Architecture's new monograph on homeland architect Juha Leiviskä gives the impression that it is part of a series. It does in fact follow — by more than 20 years, though — Juha Leiviskä 1964–1999, also published by the MFA. At 10 by 13 inches and 263 pages, the new monograph is large, featuring 21 works spanning two decades, with generously sized photographs accompanied by drawings and text by Leiviskä, the last in Finnish and English. I first became aware of Leiviskä's buildings during architecture school in the first half of the nineties, having seen his beautiful and distinctive churches in magazines, including an issue of A+U dedicated to him. The churches — marked by tightly spaced parallel walls, generous yet selective glazing, and stunning natural light (accompanied by numerous pendant lamps designed by the architect) — are what Leiviskä is known for. Given the chronological ordering of the two monographs, each one covering 20 to 25 years, readers will not find the Männisto Church in Kuopio, Myyrmäki Church in Vantaa (both of them are in Henry Plummer's Nordic Light), and other relatively famous pre-2000 buildings among the 21 works. But the Church of the Good Shepherd (Hyvän Paimenen kirkko) in Pakila reveals the continuity of his design approach, while non-ecclesiastical buildings like the Swedish School of Social Science at the University of Helsinki and the Dar Al-Kalima Academy/Ad Dar Cultural Centre in Bethlehem shows the applicability of his method to other typologies and geographies.

|

| Spread from Juha Leiviskä 2000–2022, courtesy of bookm-ark.fi |

Coming before the nearly two-dozen projects that make up the bulk of the book are four texts. First is a short but heavily illustrated background by the architect that highlights some of the key people and moments, spanning from childhood and architecture school to an impressionable meeting with German architect Heinz Bienefeld before he died in 1995. Leiviskä does not delve into his years of practice, but that is taken up by editor Elina Standertskjöld in "Perspectives on Juha Leiviskä's Oeuvre," which comments on the projects that follow and puts them into a wider context. Third is "Space, Light, Music: The Architectural Vision of Juha Leiviskä" by architectural historian William J. R. Curtis, who, like me, first became acquainted with the work of Leiviskä in the early 1990s but subsequently wrote numerous essays on the architect in magazines and included him in the third edition (1996) of his Modern Architecture Since 1900. Last is "Light, structure and rhythm: Juha Leiviskä and the Baroque" by Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen, architect and professor at Aalto University, who links Leiviskä thoroughly modern architecture to Baroque traditions. These essays (in English; in Finnish in the back matter) are all valuable, as are the project descriptions, where the architect's voice is clear and insightful. A highlight of the latter is Leiviskä recounting his decision to participate in the controversial Guggenheim Helsinki competition: "Should they take the unfortunate decision to build a Guggenheim in Helsinki, surely they need to have at least one sound proposal."

|

| Spread from Shigeru Ban: Timber in Architecture, courtesy of Rizzoli |

In 2009, Rizzoli published Shigeru Ban: Paper in Architecture, a monograph on one aspect of the Japanese architect's creations. While I'm not sure if that book was planned as a series, it makes sense that a series of material-focused monographs on the built work of Shigeru Ban would start with paper — think of the cardboard tubes he has used for emergency shelters, temporary exhibition venues, etc. — before moving on to other materials, most notably wood and bamboo. The time certainly wasn't right for Timber in Architecture back in 2009, but the numerous buildings Ban has structured in mass timber over the last decade make the new book more than welcome. These years saw Ban designing museums, office buildings, and other non-humanitarian projects almost exclusively in wood — or at least parts of each building in wood. A notable example is the Tamedia Office Building in Zurich, whose monolithic, dry-fit, highly expressive timber frame I saw under construction in 2012 and then behind glass in 2013 (seeing a giant wood-frame construction in a city center was jarring, I'll admit, though also a good sign of things to come). More architecturally daring is the Centre Pompidou-Metz, shown here in spreads, a melding of "the structural form of Frei Otto's cable net roofs and the architectonic qualities of a traditional Chinese hat," per the description in the book. Presented in project form in Paper in Architecture, the museum was completed one year later, in 2010.

|

| Spread from Shigeru Ban: Timber in Architecture, courtesy of Rizzoli |

A monograph, series or not, focused on a single material means providing information that goes well beyond a typical monograph. While neither the paper nor timber books are as technical as the earlier Shigeru Ban monograph by Matilda McQuaid (each chapter in that 2003 book, it should be noted, corresponded with one of Ban's frequently used materials: paper, wood, bamboo, etc.), each provides highly illustrative axonometrics whose coloring clearly shows the extents of the title material. The two spreads here show how those axons range from small-scale exploded views free of notes to highly detailed assembly diagrams that label the various parts required to enable the construction. Without these diagrams, born in part from a cognizance of the importance of mass timber in 21st-century architecture, this monograph would be less valuable and hardly worthy of inclusion in this post. With them, the book provides information that exceeds what is available on Shigeru Ban's website, and it gives architects interested in mass timber inspiration for using the material in their projects. Is bamboo the next monograph? Hopefully we won't have to wait another thirteen years to find out.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated for spam.