Finding Fay: Thorncrown Chapel

Posts have been a little slim lately, owing to being on a family vacation. This week I managed to drag a few non-architects to see two renowned chapels by Arkansan E. Fay Jones, one completed in 1980 and one in 1988. The first is, obviously, Thorncrown Chapel, located in Eureka Springs, Arkansas (the second, Mildred B. Cooper Memorial Chapel, will be the subject of my next post). It's a building I included in last year's 100 Years, 100 Buildings, but I didn't get the chance to see it in person until just the other day.

[Spread from 100 Years, 100 Buildings]

Finding the chapel is pretty easy, given that the building has its own website and there explains that "Thorncrown Chapel is located a mile and a half west of Eureka Springs on Hwy 62 West. GPS often does not show the correct location of the chapel. For an accurate map click here." With a smartphone, that Google Maps link makes navigation easy, as do the historical-marker signs along 62. I'll admit the winding drive through dense forests is an often breathtaking one – with glimpses of misty foothills and rivers I wasn't able to catch on camera – and an important part of experiencing the remote chapel.

[The unassuming yet fairly clear entrance to Thorncrown Chapel | Photo: Google Street View]

Before arriving at the chapel, one comes across two other buildings on the property. First is the Worship Center, which Jones designed later with his partner Maurice Jennings. This building, which looks more like a traditional church, was completed in 1989 due to the high demand to use the chapel for weddings and worship services. It is located to the left of the entrance drive and is reached via a small bridge. (Note: Photos from here on out are my own.)

Second is a small office that sits by the parking lot, adjacent to the walkway leading to the chapel. I'm not sure if Jones designed it, but the expressive structure certainly fits with Jones's Wright-inspired yet clearly personal style of architecture. (Note: the foggy effect is due to mist forming on the lens after getting out of the car and stepping into the humidity.)

The chapel sits at the end of a slightly winding stone path, a postcard view that is that much better in person.

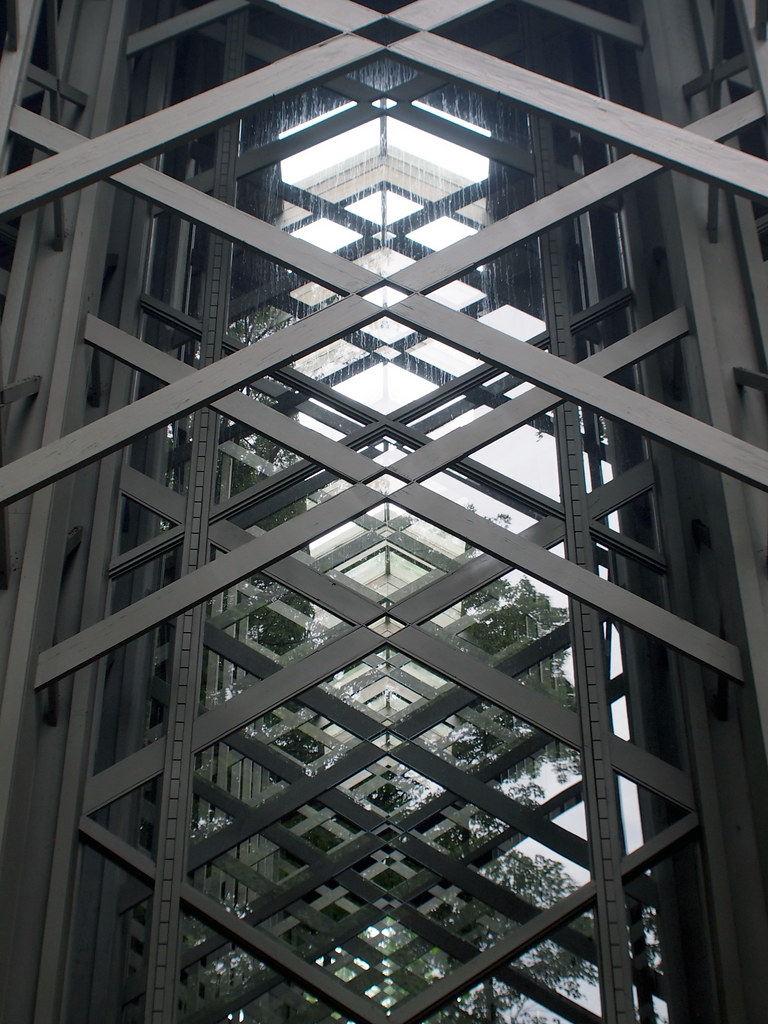

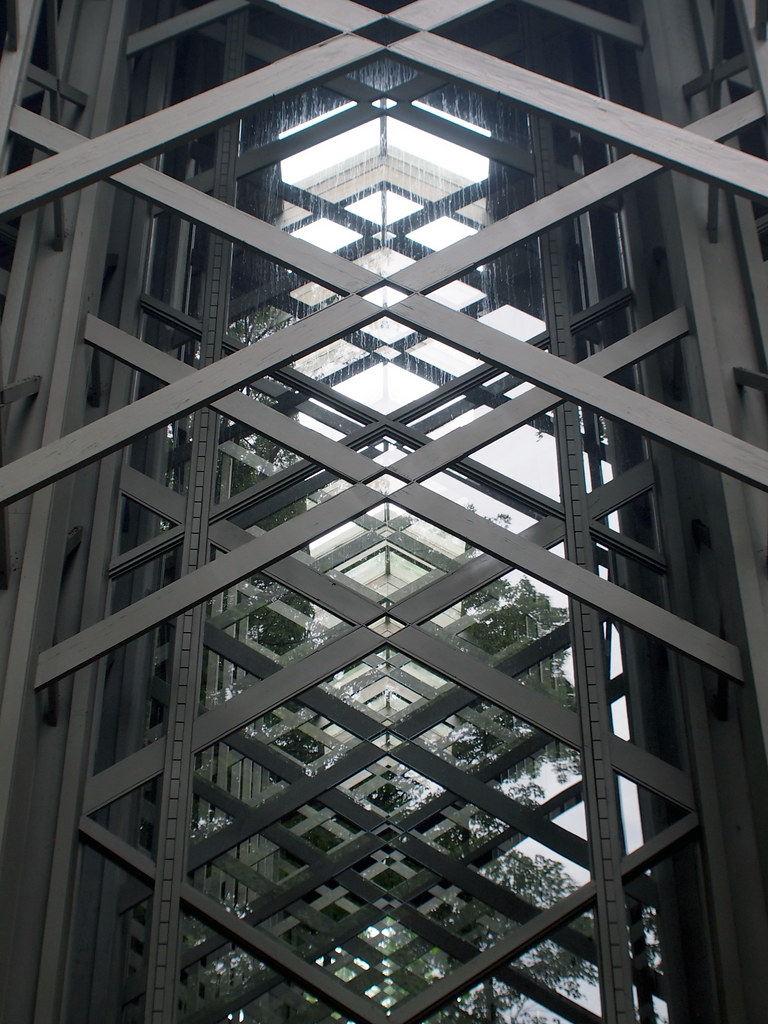

The rain that preceded our visit left some streaks on the glass, making the building a little less transparent than ideal conditions, but my favorite detail still stood out. I'm referring to the hollow steel joints that connect the two halves of the trusses and cross-braces down the middle of the space. In 100 Years, 100 Buildings, I wrote: "[These] smaller diamond-shaped openings are a symbol of the infinite or perhaps the beyond."

Once inside, visitors are asked to be seated, from where they can take photos. This seemed odd at first, but I appreciated it, since people weren't walking up and down the aisle snapping photos as they glanced up at the lattice-like structure of standard lumber.

In my short stay inside the chapel, my mind seemed to bounce back and forth between calm – just enjoying being in the space – and honing in on the structure's myriad details. The alignment of the stone base with the pews was one such detail, one that seemed to accentuate the framing of the thick forest through the glass panes above the base.

And of course there were the light fixtures mounted to the wood frame, a Wrightian detail that fits with the chapel but doesn't overwhelm it.

There's no path to circumnavigate the chapel, but it's still possible to get a glance at the side elevations, where the repetitious verticals almost converge into a solid wall.

Heading on our way, we tried to access the Worship Center, but it was closed – one volunteer was in the chapel, so I'm guessing a second would have been needed to give access to both structures.

Nevertheless, we could traverse the bridge and peek in the gap between the doors. From even this smallest of glimpses, it was possible to ascertain how this building's glazed view is about a vista rather than the intimacy of the forest, as in the chapel. In this sense, the two buildings capture these polar qualities of the Ozark landscape that were partly grasped during the drive.

[Spread from 100 Years, 100 Buildings]

Finding the chapel is pretty easy, given that the building has its own website and there explains that "Thorncrown Chapel is located a mile and a half west of Eureka Springs on Hwy 62 West. GPS often does not show the correct location of the chapel. For an accurate map click here." With a smartphone, that Google Maps link makes navigation easy, as do the historical-marker signs along 62. I'll admit the winding drive through dense forests is an often breathtaking one – with glimpses of misty foothills and rivers I wasn't able to catch on camera – and an important part of experiencing the remote chapel.

[The unassuming yet fairly clear entrance to Thorncrown Chapel | Photo: Google Street View]

Before arriving at the chapel, one comes across two other buildings on the property. First is the Worship Center, which Jones designed later with his partner Maurice Jennings. This building, which looks more like a traditional church, was completed in 1989 due to the high demand to use the chapel for weddings and worship services. It is located to the left of the entrance drive and is reached via a small bridge. (Note: Photos from here on out are my own.)

Second is a small office that sits by the parking lot, adjacent to the walkway leading to the chapel. I'm not sure if Jones designed it, but the expressive structure certainly fits with Jones's Wright-inspired yet clearly personal style of architecture. (Note: the foggy effect is due to mist forming on the lens after getting out of the car and stepping into the humidity.)

The chapel sits at the end of a slightly winding stone path, a postcard view that is that much better in person.

The rain that preceded our visit left some streaks on the glass, making the building a little less transparent than ideal conditions, but my favorite detail still stood out. I'm referring to the hollow steel joints that connect the two halves of the trusses and cross-braces down the middle of the space. In 100 Years, 100 Buildings, I wrote: "[These] smaller diamond-shaped openings are a symbol of the infinite or perhaps the beyond."

Once inside, visitors are asked to be seated, from where they can take photos. This seemed odd at first, but I appreciated it, since people weren't walking up and down the aisle snapping photos as they glanced up at the lattice-like structure of standard lumber.

In my short stay inside the chapel, my mind seemed to bounce back and forth between calm – just enjoying being in the space – and honing in on the structure's myriad details. The alignment of the stone base with the pews was one such detail, one that seemed to accentuate the framing of the thick forest through the glass panes above the base.

And of course there were the light fixtures mounted to the wood frame, a Wrightian detail that fits with the chapel but doesn't overwhelm it.

There's no path to circumnavigate the chapel, but it's still possible to get a glance at the side elevations, where the repetitious verticals almost converge into a solid wall.

Heading on our way, we tried to access the Worship Center, but it was closed – one volunteer was in the chapel, so I'm guessing a second would have been needed to give access to both structures.

Nevertheless, we could traverse the bridge and peek in the gap between the doors. From even this smallest of glimpses, it was possible to ascertain how this building's glazed view is about a vista rather than the intimacy of the forest, as in the chapel. In this sense, the two buildings capture these polar qualities of the Ozark landscape that were partly grasped during the drive.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated for spam.