Architecture Unbound

Architecture Unbound: A Century of the Disruptive Avant-Garde

by Joseph Giovannini

Rizzoli, November 2021

Hardcover | 9 x 11 inches | 876 pages | 698 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9780847858798 | $50.00

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

SPREADS:

by Joseph Giovannini

Rizzoli, November 2021

Hardcover | 9 x 11 inches | 876 pages | 698 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9780847858798 | $50.00

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

In Architecture Unbound, noted architecture critic Joseph Giovannini proposes that our current architectural landscape ultimately emerged from transgressive and progressive art movements that had roiled Europe before and after World War I. By the 1960s, social unrest and cultural disruption opened the way for investigations into an inventive, antiauthoritarian architecture. Explorations emerged in the 1970s, and built projects surfaced in the 1980s, taking digital form in the 1990s, with large-scale projects finally landing on the far side of the millennium.

Architecture Unbound traces all of these developments and influences, presenting an authoritative and illuminating history not only of the sources of contemporary currents in architecture but also of the twentieth-century avant-garde and the twenty-first-century digital revolution in form-making, and profiling the most influential practitioners and their most notable projects, including Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao and Walt Disney Concert Hall, Zaha Hadid’s Guangzhou Opera House, Daniel Libeskind’s master plan for the World Trade Center, Rem Koolhaas’s CCTV Tower, and Herzog and de Meuron’s Bird’s Nest Olympic Stadium in Beijing.

Joseph Giovannini is a practicing architect who has written on architecture and design for three decades for such publications as the New York Times, Architectural Record, Art in America, and Art Forum, and he has served as the architecture critic for New York magazine and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner.

REFERRAL LINKS:

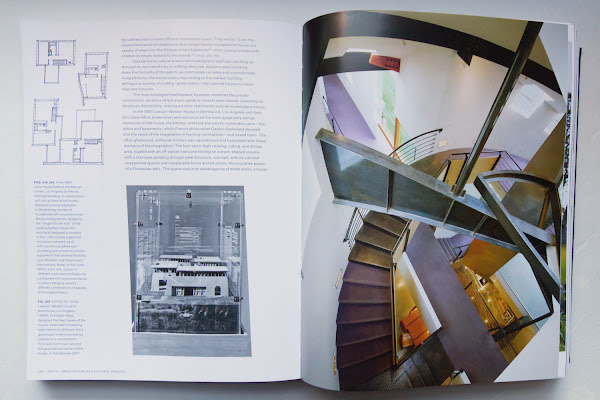

On June 23, 1988, Deconstructivist Architecture opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Organized by former MoMA curator Philip Johnson and architectural theorist Mark Wigley, the influential exhibition presented the work of seven architects "obsessed with twisted shapes, warped planes, and folded lines": Coop Himmelb(l)au (Wolf Prix and Helmut Swiczinsky), Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, and Bernard Tschumi. Three of the architects would go on to win Pritzker Prizes and all of them would go on to have successful practices realizing large-scale projects around the world.

Visitors to the exhibition at MoMA — not to mention people who did not see the show but learned about it later, like myself, through its catalog and the subsequent work of the seven architects — would be forgiven for thinking that Johnson and Wigley discovered the architects and any apparent strands binding them, no matter how superficial their readings or tenuous the connections. But buried in the catalog's acknowledgements — the part of a book I used to skip over but now gravitate to — Johnson mentions Aaron Betsky, who "called [his] attention to the telling phrase 'violated perfection'" (also the title of a book Betsky would put out in 1990); Paul Florian and Stephen Wierzbowski, who first proposed an exhibition with that title; and Joseph Giovannini, "another valuable source of preliminary information on the subject."

Clearly, numerous people in the late 1980s were cognizant of changes in architecture that were moving the discipline beyond Postmodernism and toward fragmented and disjointed forms that served to provoke and express instability rather than harken to a supposed stable past through the ironic use of historical forms. As such, it isn't necessarily crucial to peg down who discovered or articulated the "movement" first, but it is curious to find out how Deconstruction, the philosophy coined by Jacques Derrida that influenced some architects at the time, most notably Peter Eisenman, got mashed up with Constructivism, the early 20th-century art movement in Russia that most visibly found influence in the paintings of Zaha Hadid.

Giovannini, in the introduction to his magisterial Architecture Unbound, which just came out but was primarily written between 1987 and 1992, the architecture critic explains how he created the "Deconstructivist" neologism from "influences in the way architects were inviting other disparate disciplines into their designs." The two terms had little to do with each other, he admits, but he found it an apt description to the work of Gehry, Hadid, and others at the time and a fitting name for the book he was working on. But then, in the middle of 1987, Giovannini went and told Johnson about The Deconstructivists, which would eventually become Architecture Unbound, only to hear later in the year about the exhibition that would soon be opening at MoMA: Deconstructivist Architecture.

Although Giovannini describes the background of "Deconstructivism" and the gestation of Architecture Unbound in lengthy sidebars set apart from the main text through the use of smaller, blue text, it's clear throughout the book that it was written by someone embedded within (avant-garde) architectural culture. Though I have not met him, Giovannini, a practicing architect as well as a writer, reminds me of Herbert Muschamp, in the way the late New York Times critic got close to his subjects personally, fostered relationships with them over time, and played favorites with some of them in his writings. Not only is Giovannini's animosity toward Johnson palpable at times in Architecture Unbound, the roll call of architects in the book, which focuses on the late 1980s and early 1990s but also brings things to the present, is tight, focused on the seven architects in the MoMA show and a few others beyond them.

Don't get me wrong, there are many more than a dozen or so architects in Giovannini's thematic, non-chronological presentation of avant-garde architecture, but the ones he returns to frequently are few; they are the ones who have wielded the most influence in the early years of Deconstructivism and in the decades since. Some of the other architects include Günter Behnisch, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Enric Miralles, and Thom Mayne, to name a few, plus a trio of architects who are given their own chapter-length profiles (the only such profiles in the book): Claude Parent, Lebbeus Woods, and Manfred Wolff-Plottegg. Parent, a "radical in bourgeois camouflage," according to Giovannini, who "prefigured Deconstructivism by a generation," is given fifty pages (compared to ten for each of the other two profiles) and is referred to often in the rest of the book.

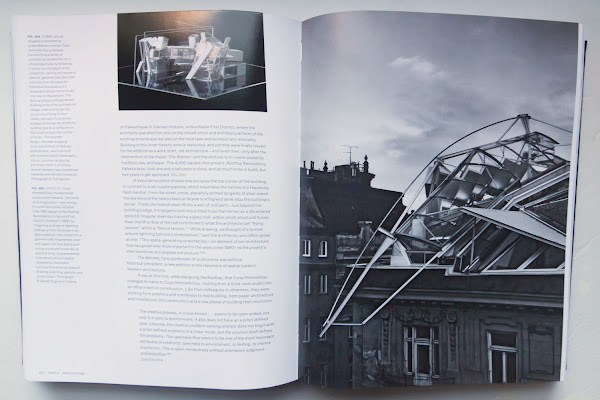

Claude Parent's anticipation of Gehry, Tschumi, Hadid, and others makes him a fitting subject for a profile, and I have a hard time questioning one on Lebbeus Woods in a book on avant-garde architecture, but I'm perplexed by the inclusion of Austrian architect Manfred Wolff-Plottegg, who I was not familiar with before seeing Giovannini's book. If the earlier surveys of Austrian architecture published in 1999 and 2016 are any indication, his most important work is the Seiersberg Housing Complex completed in Graz in 1991 and designed from an exclusively computer-generated planning process. Giovannini calls the Graz-based architect "a one-man epicenter of nearly all the issues of the alternative architecture practiced by the more visible avant-garde." It was "his breakthrough work on the computer," he continues, that "contributed to the larger shift occurring in architecture."

So Plottegg, as a hinge between the angular fragmentation of Deconstructivism and the blobs and other smooth surfaces of architecture "in the computer," is a suitable presence in Architecture Unbound even though he's overshadowed by Coop Himmelb(l)au and other avant-garde Austrian architects. Nevertheless it comes across that Giovannini, who penned the introduction to the 2015 monograph on Plottegg, Architecture Beyond Inclusion and Identity is Exclusion and Difference from Art, is playing favorites by singling out Plottegg as one of just three profiles in his massive book. Whatever the case, his inclusion is welcome, as are the inclusion of the other architects exploring similar avant-garde tendencies; they help make Architecture Unbound a voluminous resource and must-have reference on an exciting period of architectural form-making.

SPREADS: