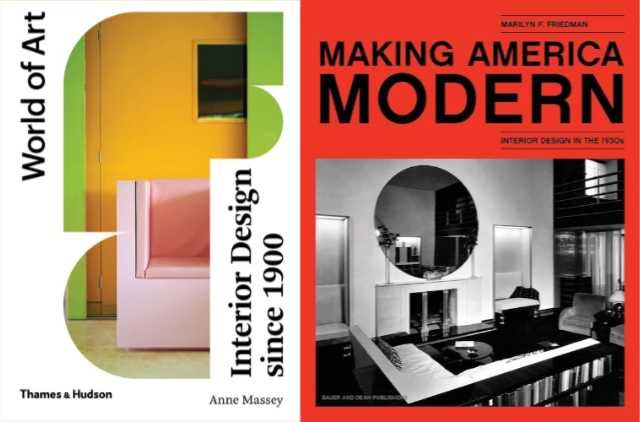

Two Interior Design Books

Interior Design since 1900, Fourth Edition

by Anne Massey

Thames & Hudson, April 2020

Paperback | 6 x 8-1/4 inches | 272 pages | 229 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9780500204603 | $24.95

(Click here for publisher's description and author bio)

Interior Design since 1900 is both a history and a survey, meaning it is full of projects, many of them discussed only briefly given the enormous subject and limited space, but it also looks wider to other undertakings impacting the fields related to interiors, such as education and publications. The latter is particularly interesting to me and helpful in the context of this review. Massey was the founding editor of the journal Interiors: Design, Architecture, Culture, so it shouldn't be a surprise that she seems to be aware of every important publication on interiors, many of them mentioned in the book. (Unfortunately the books and journals are not included in the index, only their authors, which makes it hard to find some of the publications again.)

by Anne Massey

Thames & Hudson, April 2020

Paperback | 6 x 8-1/4 inches | 272 pages | 229 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9780500204603 | $24.95

(Click here for publisher's description and author bio)

REFERRAL LINKS:

Making America Modern: Interior Design in the 1930s

by Marilyn F. Friedman

Bauer and Dean Publishers, May 2018

Hardcover | 8-1/2 x 10-1/2 inches | 240 pages | 205 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9780983863236 | $50.00

(Click here for publisher's description and author bio)

by Marilyn F. Friedman

Bauer and Dean Publishers, May 2018

Hardcover | 8-1/2 x 10-1/2 inches | 240 pages | 205 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9780983863236 | $50.00

(Click here for publisher's description and author bio)

REFERRAL LINKS:

REVIEW:

Although Amazon's algorithmic categorizations are perplexing at times, and I'm guessing most people find books on Amazon via searches rather than browsing in categories, there is something telling when comparing the top books in the "Architecture" category to those in the "Interior & Home Design" category: they are the same and, accordingly, they are all books on interior design. This does not surprise me, since books on interior design are more accessible and relevant to a wider audience, not just professionals. Homeowners who would never entertain hiring an architect, and who therefore don't have a need for any architecture books, can easily decorate or redecorate their interiors themselves, finding inspiration in books as well as websites like Houzz and apps like Pinterest.

Higher sales for interior design books compared to architecture books is therefore logical, but can one say that interiors scholarship is on par with architecture? I'm guessing interior designers would say "yes," but my knowledge and familiarity with interior design titles is limited so I have a hard time offering up an answer. Nevertheless it's a question that seems worth exploring, at least in the context of these two books on interior design.

|

| Screenshot of Amazon's top titles in "Architecture" and "Interior & Home Design" categories. |

Anne Massey's Interior Design since 1900 was first published in 1990, when it was titled Interior Design of the 20th Century. Like other books on art and architecture in Thames & Hudson's extensive World of Art series, such as Kenneth Frampton's seminal Modern Architecture: A Critical History, Massey has updated her history and survey of interior design regularly: in 1996, 2008, and most recently in 2020 (the new millennium, it goes without saying, necessitated the change in titles). In each update a new chapter was added at the end, with "The Post-modern Era" added in '96, "The Sustainability of Interior Design" in '08, and "Transnational Interiors" a couple of years ago.

The fourth edition spans from "Reforming Victorian Taste" in the late 1800s to the 2010s, with numerous chapters on various forms of modernism in between. It is a lot of room to cover, especially considering that the book starts in a clearly British context but ends in one that is international. While Massey does pull important examples from beyond the British Isles, it is never long before she returns to projects in the UK or designed by British designers; I'm guessing the professor of design history at Kingston University in London is tapping into what she is most familiar with. By the the last chapter and its look at how countries have used design to express their independence, it's not surprising to see a plethora of former British colonies or protectorates: India, Singapore, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and the UAE.

|

| Spread from Interior Design since 1900, courtesy of Thames & Hudson |

Interior Design since 1900 is both a history and a survey, meaning it is full of projects, many of them discussed only briefly given the enormous subject and limited space, but it also looks wider to other undertakings impacting the fields related to interiors, such as education and publications. The latter is particularly interesting to me and helpful in the context of this review. Massey was the founding editor of the journal Interiors: Design, Architecture, Culture, so it shouldn't be a surprise that she seems to be aware of every important publication on interiors, many of them mentioned in the book. (Unfortunately the books and journals are not included in the index, only their authors, which makes it hard to find some of the publications again.)

One example is found in the chapter on sustainability, when Massey writes about "a growing tendency among interior designers to develop as reflective practitioners, taking theoretical issues into account," such that "the study of the interior is now more academically respectable." She then lists a handful of relevant books, including INTIMUS: Interior Design Theory Reader from 2006 but none after 2008, since the chapter was, mind you, part of the third edition put out that year. A select bibliography in the back matter expands upon the publications mentioned in the book, giving people interested in interior design scholarship plenty to consider.

If Interior Design since 1900 is correct (and I'm pretty sure it is) in stating "modernism continues to be the the all-pervasive style, whether for luxury apartments, airports or shopping centers," how did early modern interiors spread to influence clients and designers to adopt modernism over traditional styles? For Marilyn F. Friedman, "a design historian whose work focuses on the development and popularization of modern design across America," it happened, in the United States at least, in the 1920s and 30s. The same could actually be said about Europe, with the houses of Le Corbusier in the 1920s, the Bauhaus moving to Dessau in 1925, and other instances of modernism being propagated then, but how did it happen in the US?

|

| Spread from Interior Design since 1900, courtesy of Thames & Hudson |

If Interior Design since 1900 is correct (and I'm pretty sure it is) in stating "modernism continues to be the the all-pervasive style, whether for luxury apartments, airports or shopping centers," how did early modern interiors spread to influence clients and designers to adopt modernism over traditional styles? For Marilyn F. Friedman, "a design historian whose work focuses on the development and popularization of modern design across America," it happened, in the United States at least, in the 1920s and 30s. The same could actually be said about Europe, with the houses of Le Corbusier in the 1920s, the Bauhaus moving to Dessau in 1925, and other instances of modernism being propagated then, but how did it happen in the US?

Friedman explores a particular aspect of it in her first book, Selling Good Design: Promoting the Early Modern Interior, published by Rizzoli in 2003: "how prestigious and trend-setting New York department stores introduced modern design, especially Art Deco, to the press and the public during the late 1920s." Spreading modernism in the places where people shop, and where they might spend their money on modern updates to their homes, is an intriguing idea that also makes a lot of sense. To me, the idea is strengthened by the fact MoMA's Modern Architecture: International Exhibition toured the United States after its run at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932, with two of the fourteen stops actually being department stores (that was something I learned about in Terence Riley's invaluable book on the exhibition, The International Style: Exhibition 15 and The Museum of Modern Art).

Friedman's latest book, Making America Modern: Interior Design in the 1930s, picks up where Selling Good Design left off, giving a year-by-year account of exhibitions, projects, publications, and other output that show modern design spreading across the United States. Logically, the prologue gives some background from the second half of the 1920s, basically serving as a 15-page recap of Friedman's first book, with illustrations of exhibitions at Abraham & Straus, Frederick Loeser & Co., Lord & Taylor, and R.H. Macy & Co. Department stores are occasional venues in the ten chronological chapters that follow, but most of the text and images in the ten chapters are devoted to museum exhibitions and residential projects.

|

| Spread from Making America Modern, courtesy of book designer Matthew Egan |

Friedman's latest book, Making America Modern: Interior Design in the 1930s, picks up where Selling Good Design left off, giving a year-by-year account of exhibitions, projects, publications, and other output that show modern design spreading across the United States. Logically, the prologue gives some background from the second half of the 1920s, basically serving as a 15-page recap of Friedman's first book, with illustrations of exhibitions at Abraham & Straus, Frederick Loeser & Co., Lord & Taylor, and R.H. Macy & Co. Department stores are occasional venues in the ten chronological chapters that follow, but most of the text and images in the ten chapters are devoted to museum exhibitions and residential projects.

A handy table of contents lists the exhibitions and projects that appear in each chapter; here we see many names of designers repeating: Donald Deskey, Joseph Aronson, William Lescaze, Rudolph Schindler, Paul T. Frankl, Frederick Kiesler, George Keck, and Russell Wright. Exhibitions include the AUDAC exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 1931, the Design for the Machine exhibition at the Pennsylvania Museum of Art in 1932 (MoMA's exhibition of the same year is missing though), the model houses at the Chicago World's Fair in 1933, the Metropolitan Museum of Art's exhibition of American industrial arts in 1934, and relevant exhibits at the New York World's Fair in 1939, among others. The book closes in 1940, with an epilogue devoted to the America at Home exhibition that opened at the New York World's Fair in May 1940.

As these few spreads indicate, the bold black/white/red graphics on the cover continues inside the book, with red pages signaling the chapters, red text used for the book and chapter titles at the bottom of the pages, and red quotes used for the block quotations inserted between paragraphs; the abundance of black-and-white photographs in the couple of hundred illustrations makes the small amounts of red in the text pop. Furthermore, the way the red covers wrap around to the endpapers — those, it should be noted, are covered in an image of a zebra-print fabric that appears period but is still made today — it's like the open book has a red frame. All this is to say that the book, as designed by Matthew Egan, is beautiful, a perfect match to its subject.

|

| Spread from Making America Modern, courtesy of book designer Matthew Egan |

As these few spreads indicate, the bold black/white/red graphics on the cover continues inside the book, with red pages signaling the chapters, red text used for the book and chapter titles at the bottom of the pages, and red quotes used for the block quotations inserted between paragraphs; the abundance of black-and-white photographs in the couple of hundred illustrations makes the small amounts of red in the text pop. Furthermore, the way the red covers wrap around to the endpapers — those, it should be noted, are covered in an image of a zebra-print fabric that appears period but is still made today — it's like the open book has a red frame. All this is to say that the book, as designed by Matthew Egan, is beautiful, a perfect match to its subject.

Friedman's year-by-year account of modern interior design in America in the 1930s is remarkably thorough and well researched, with words that are as descriptive as the photographs accompanying them. Fifteen years in the making, Making America Modern has more than four hundred footnotes and an eight-page selected bibliography; the latter comprises more magazine articles than books, signaling to me that scholarship on interior design relies on writers like Friedman to synthesize contemporary accounts into historical accounts that capably brings designs together and put them into larger contexts.

|

| Spread from Making America Modern, courtesy of book designer Matthew Egan |