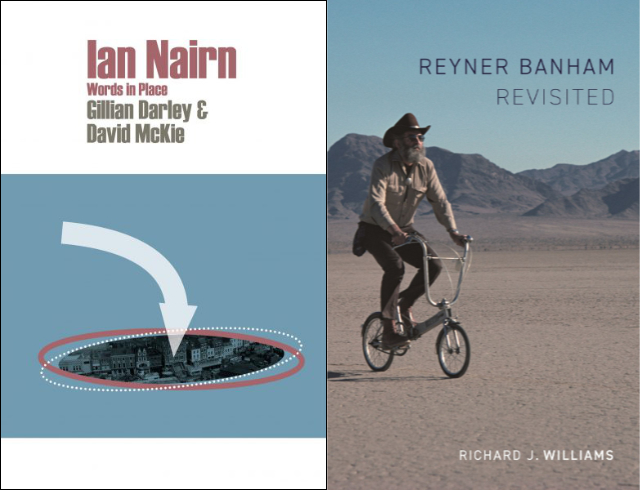

Two British Biographies

Ian Nairn: Words in Place

by Gillian Darley and David McKie

Five Leaves Publications, November 2013

Hardcover | 6 x 9 inches | 160 pages | 21 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781907869877 | £10.99 | "Ian Nairn taught a generation to look, and another one to write." (click here for publisher's description and author bio)

REFERRAL LINKS:

Reyner Banham Revisited

by Richard J. Williams

Reaktion Books, July 2021

Hardcover | 5-1/2 x 8-1/2 inches | 304 pages | 55 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781789144178 | $35.00 | "Banham’s obsession with technology, and his talent for thinking the unthinkable, mean his work still resonates now, more than thirty years after his death." (click here for publisher's description and author bio)

REFERRAL LINKS:

FOR FURTHER READING:

by Gillian Darley and David McKie

Five Leaves Publications, November 2013

Hardcover | 6 x 9 inches | 160 pages | 21 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781907869877 | £10.99 | "Ian Nairn taught a generation to look, and another one to write." (click here for publisher's description and author bio)

REFERRAL LINKS:

Reyner Banham Revisited

by Richard J. Williams

Reaktion Books, July 2021

Hardcover | 5-1/2 x 8-1/2 inches | 304 pages | 55 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781789144178 | $35.00 | "Banham’s obsession with technology, and his talent for thinking the unthinkable, mean his work still resonates now, more than thirty years after his death." (click here for publisher's description and author bio)

REFERRAL LINKS:

REVIEW:

Of the 100 books surveyed in my latest book, Buildings in Print, there are very few architects/authors with multiple titles. Both Le Corbusier and Rem Koolhaas have four titles — not surprising, since both architects use(d) books as extensions of their building practices — and then comes Reyner Banham with three books: Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment, and Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies. Peter Reyner Banham (1922–1988) was an architectural writer, and one of the best, so books were clearly an important media for him. But given that one can count all of the books he wrote on just two hands (the number is eight, from Theory and Design in 1960 to A Concrete Atlantis in 1986), he wrote an impressive number of seminal books, a much higher percentage than Le Corbusier (he wrote ~50 books), Koolhaas (~20 books), and anyone else I can think of.

Even though the quality of Banham's writing extends to the published articles he wrote, the essays he contributed to books by others, and even the TV and radio appearances he made, books are what have defined the life of Reyner Banham. Therefore it makes sense that a biography of Banham would be structured according to his books, which is exactly what Richard J. Williams has done with Reyner Banham Revisited. More accurately, Williams uses Banham's books to define seven personas, or hats that Banham donned throughout his working life: "The Futurist" of Theory and Design, for example, and "The Environmentalist" of Well-Tempered Environment. But Williams does not restrict his biography to Banham's books, since "they were only a fraction of the overall output," as he writes in the preface. Williams brings Banham's journalism, documentaries, and other output into the fold, painting a nuanced and complex, if incomplete, picture of the critic's life.

The incomplete nature of the biography is hardly due to Williams, who is attentive in his readings of Banham and thorough in his research. Some of the latter took place at the Getty, where the Banham Papers are located, but as Williams admits, Banham destroyed most of his notes and first drafts. Williams isn't even sure first drafts were ever made, instead finding in Banham a remarkable ability to swiftly produce a final draft after ruminating on a subject over a period of time — as a journalist, not just a historian and critic, that time was often quite short. So when Williams tries to link Banham's experiences during World War II, when he worked on engines for warplanes and was discharged "following a physical and mental breakdown," according to Williams, Banham's own printed words on the traumatic period are scarce, usually summed up as "a series of amusing anecdotes" according to Ben Banham, who Williams spoke with to fill in the gaps.

As Williams moves from Banham the "Futurist" to Banham the "Autophile," "Angeleno," "Desert Freak" and beyond, he does not attempt to delve deeply into Banham's personal experiences to the point of exposé. More so, the goal is to try to define Banham as a person of many personalities, someone who was able to write approximately 1,000 articles as a journalist yet also maintain academic posts. His first book was a slight reworking of his PhD — and reads as such — but later books and articles are much more accessible and enjoyable, clearly indicating that his path was not set from a young age. One of the main consistencies among his life of numerous "guises" is his wife, Mary Banham, who died in 2018. Although Williams mentions Mary here and there, it would have been nice to learn more about the person who inked the drawings in Well-Tempered Environment and was the apparent rock in Reyner's life, the life cut short by cancer in 1988.

Another British critic who died too soon is Ian Nairn (1930–1983), a relative unknown outside of the UK compared to Banham. That's not for lack of trying, though, as Nairn's sixth book (or fourth, depending on how one defines them) was The American Landscape: A Critical View, in which the barbed-wire critic applied the fury he previously focused on London and the "subtopia" around it to the much larger canvas of the United States. Outrage and Counter-attack against Subtopia (published by Architectural Press in 1955 and 1957, each was first a special issue of Architecture Review, hence the confusion in attributing them as books) brought Nairn some acclaim right out of the gate, pushing him into the spotlight and onto televisions in the UK, turning him into a champion of the people and the enemy of modern planning and (bad) modern architecture. The 1965 book about the United States is unfocused by comparison, combining attributes of Gordon Cullen's Townscape with Peter Blake's God's Own Junkyard; Nairn biographers Gillian Darley and David McKie see "an immediate dissonance" between the good and bad he found in America.

Like Richard J. Williams with Banham, Darley and McKie use Nairn's output — books mainly, but also newspaper columns and documentaries — to structure their now-out-of-print book on the critic. The authors write in the chapter devoted to Nairn's time in the United States that part of the reason A Critical View was unfocused and could not live up to the ambition that secured him a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation (he would have produced a book of visual rules on the shape and pattern of city centers, akin to Townscape in the UK) was because the British critic was "at sea." Nairn, it seems, was most comfortable in the places he knew best, even if he detested the buildings and landscapes that comprised them. One such place was Surrey, where he grew up and where he co-wrote the first of two contributions to Nikolaus Pevsner's 46-strong Buildings of England series, published between 1951 and 1974. Nairn's contributions to the series are the subject of the third chapter in Words in Place, though he has been known best for the other guides he wrote by himself.

Nairn's London and Nairn's Paris are the most famous books produced by Nairn in his short, three-decade career and are the subject of chapter five (I write "produced" since Nairn did the photos in his book, not just the words, and he was quite good as a photographer, something Darley and McKie don't spend enough time on). Each of the seven chapters in Words in Place is written by Darley and McKie but features a preamble by a British critic influenced in some way by Nairn: Owen Hatherley, Gavin Stamp, Jonathan Glancey, to name a few. The chapter on London and Paris also includes a postscript, with Andrew Saint penning the preamble and David Thomson contributing the postscript; such is the elevated importance of those two guides. If you find it odd that Thomson, a film critic, is present, note that Roger Ebert — yes, the one and only Roger Ebert — edited a reissue of Nairn's London in 2002; Ebert's introduction clearly captures how well Nairn appealed to non-architects. I have not read Nairn's London, but the words of Darley, McKie, Saint, and Thomson make it clear my library is incomplete without a copy.

While Banham died from cancer, Nairn did himself in with his drinking. "Nairn liked pubs," Ebert wrote in the introduction, "and included a lot of them in his book." Darley and McKie write that the people who worked with Nairn on the TV documentaries he starred in thought he was "wonderful before lunch," since "after lunch he would drink" and therefore work would be done for the day, since he would not be ready to go in front of the camera until the following day. A photo of Nairn, with a beer lifted to his mouth and a cigarette at the ready in his other hand, hung over his regular seat at St. George's Tavern. Perhaps his loves of drinking and pubs are what made Nairn so appealing to non-architects, and what made him a champion of the "real" places that they embody. Yes, there are other reasons Nairn was so admired — his beautiful writing, mainly — but I can't help but try to make sense of his death at the age of 53; try to link it to the passionate life that found release in articles, books, and broadcasts. Darley and McKie don't spend too many words on Nairn's end days, but the reader is rewarded for all the detail they reveal on the life of the great British writer, someone who many people these days, they write, "have yet to make his instructive and hugely enjoyable acquaintance."

FOR FURTHER READING:

Selected books by Banham:

- Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (The MIT Press, 1980, Second Edition; first published in 1960)

- The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (University of Chicago Press, 1984, Second Edition; first published in 1969)

- Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (University of California Press, 2009, Second Edition; first published in 1971)

- Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past (The Monacelli Press, 2020, Reprint Edition; first published in 1976)

- Scenes in America Deserta (Peregrine Smith, 1982)

- A Concrete Atlantis: U.S. Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture 1900-1925 (The MIT Press, 1986)

- A Critic Writes: Selected Essays by Reyner Banham, selected by Mary Banham, Paul Barker, Sutherland Lyall, and Cedric Price (University of California Press, 1996)

- Reyner Banham: Historian of the Immediate Future by Nigel Whiteley (The MIT Press, 2001)

- Reyner Banham and the Paradoxes of High Tech by Todd Gannon (Getty Research Institute, 2017)

- Outrage (The Architectural Press, 1955)

- Counter-Attack Against Subtopia (The Architectural Press, 1957)

- Surrey (Pevsner Architectural Guides: Buildings of England), with Nikolaus Pevsner (Penguin, 1962; revised by Bridget Cherry in 1971)

- The American Landscape: A Critical View (Random House, 1965)

- Nairn's London (Penguin, 1966; "revisited" by Peter Gasson in 1988; reissued in 2002, edited by Roger Ebert)

- Nairn's Paris (Notting Hill Editions, 2018, Reprint Edition; first published in 1968)