Two Louis Sullivan Books

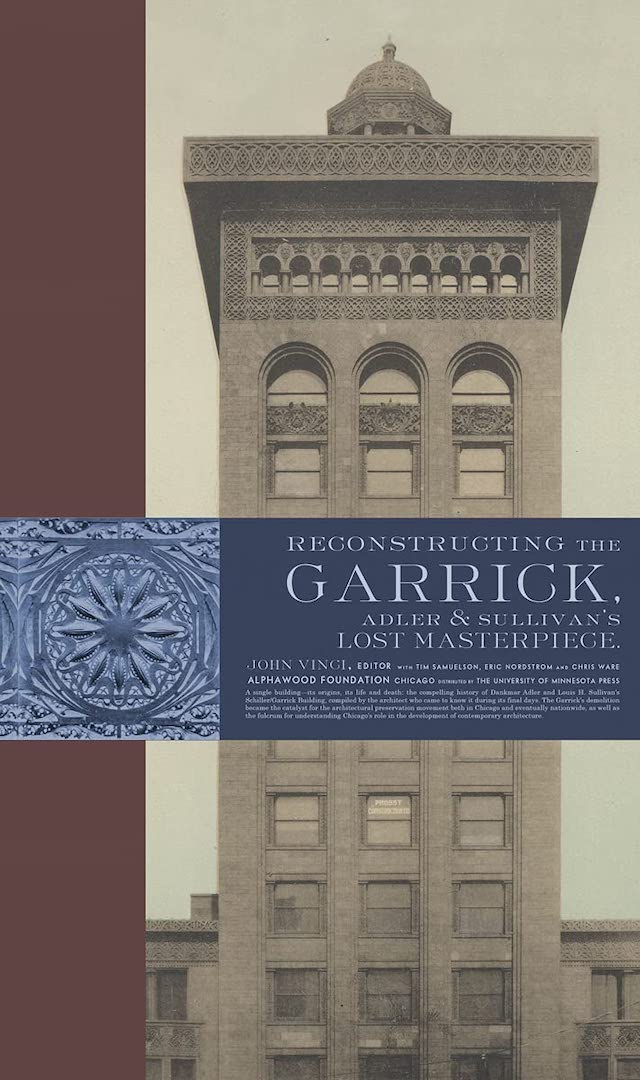

Reconstructing the Garrick: Adler & Sullivan's Lost Masterpiece

Edited by Jon Vinci, with contributions by Tim Samuelson, Eric Nordstrom, Chris Ware

Alphawood Foundation (distributed by University of Minnesota Press), October 2021

Edited by Jon Vinci, with contributions by Tim Samuelson, Eric Nordstrom, Chris Ware

Alphawood Foundation (distributed by University of Minnesota Press), October 2021

Hardcover | 8 x 13 inches | 352 pages | 250 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781517912802 | $45.00 | "A beautifully designed and lavishly illustrated biography of one of Chicago’s greatest lost buildings" (click here for publisher's description and author bio)

REFERRAL LINKS:

REVIEW:

Reconstructing the Garrick is about the Adler & Sullivan building, but it is just as much about Richard Nickel, the photographer and preservationist who salvaged parts of the Garrick and other buildings designed by Louis Sullivan. Nickel famously died in 1972 at just 43 years old when a floor in the Chicago Stock Exchange gave way during one of his salvage operations. Vinci joined Nickel in 1960 and 1961 to remove parts of the Garrick before it succumbed to the wrecking ball. Photographs of Vinci in what looks like military helmet and garb, as in the one above, give the impression that historic preservation in Chicago — any American city at the time, actually — was akin to war, pitting progress and the past against each other. This impression is furthered by the signs made for picketers (photo above), akin to the signs of anti-war demonstrators. For young people today, when historic preservation is well established but far from exciting, the documentation of the efforts to save the Garrick should be illuminating, as should the story of Nickel, who gave his life for the cause.

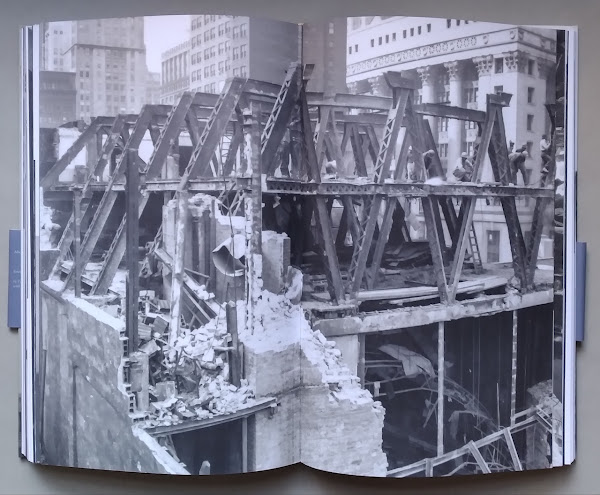

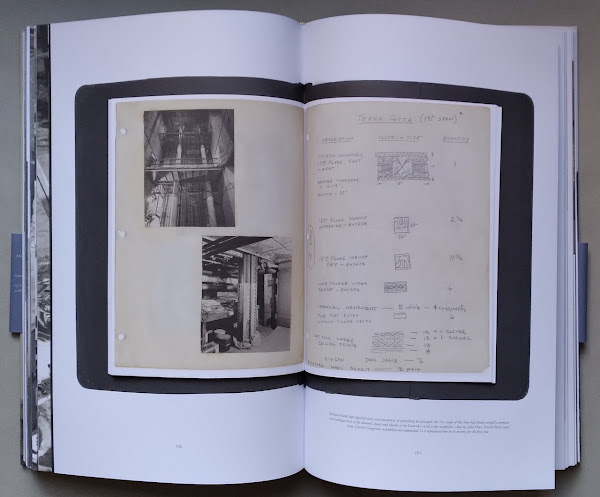

The fate of the Garrick — one among too many buildings in the Loop lost in that era — is clearly depicted in the photos of the building's demolition, some of them revealing the large trusses (above) that enabled an office tower to sit above a theater. Here readers see the building shorn of its famous ornament, which is revealed throughout the book in period photos and photographs (by Eric Nordstrom) of salvaged fragments. One of the most unexpected features of the book (there are many, the book is so rich with visual and textual delights) is a reproduction of more than seventy pages from Nickel's binder of notes; the "Ornament Salvage Workbook" is literally a book within the book, a separate stapled booklet pasted into Reconstructing the Garrick:

A photograph by John Vinci taken in 1962 (below) reveals an astounding level of irony, as the parking garage erected in place of the Garrick incorporated facade patterns recalling Sullivan's ornament (that the restaurant inserted below the garage is still called The Garrick doubles down on the irony). The caption reads, in part, that these cast concrete screens were "an apparently self-congratulatory memorial to a city pleased at having destroyed one of its major artistic monuments." Of course, the parking garage was not the goal of its demolition; it was merely a placeholder before a more modern, permanent and profitable tower could be erected, as the 50-story Chicago Title & Trust Center (now Grant Thornton Tower) was in 1992. The irony continues into the 1990s, since the skyscraper that now stands where the Garrick once did is only half of what was intended; the planned "twin" was never realized and a parking garage (behind glass and stone, not patterned concrete) sits to the north, in the footprint of the unbuilt tower.

The deepest irony is that the threats against buildings in Chicago and other American cities, while obviously leading to "lost" buildings also led to historic preservation becoming a profession and being written into law. The threats also led Nickel and others to thoroughly document buildings like the Garrick in photographs and drawings, and to act upon their love of the old buildings through protest, first, and then literal preservation of building fragments. Put another way, we wouldn't have Reconstructing the Garrick without the building's demolition, obviously, nor would we have it without the people who tried to save it. An extant Garrick Theater would be the best outcome of their efforts, but inspiring future preservationists through this publication is one of the next best things.

But that's not all! Keep scrolling to read about a second Sullivan book put out by Alphawood Foundation, the private foundation behind Wrightwood 659.

Having grown up in suburban Chicago and long been a fan of both Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, who worked for Sullivan before making a name for himself, I know a fair amount about Sullivan and his buildings, but much of it is common knowledge gleaned from architectural histories and other secondary sources. My knowledge of Sullivan is superficial compared to Samuelson, who has had a lifelong passion for the architect and exhibits that passion in these pages. He also does not hold back any critical words, such as when he describes Sullivan's only New York building, the Bayard-Condit Building (1900; spread above), as exhibiting "a stiffness uncharacteristic of Sullivan's other work." While the reader might want to chalk up this position to NYC-Chicago rivalry, Samuelson backs it up with facts about the contractor's difficulty in getting Sullivan to sign off on mockups and how Sullivan had to work with a local architect, which compromised the quality Sullivan came to expect from well established relationships in Chicago.

The surprises in Louis Sullivan's Idea are numerous, even for people familiar with Sullivan's buildings. One standout is the pedestrian bridge Sullivan designed in 1897 to connect the Schlesinger and Mayer Department Store (this was before he was hired to expand the store on State Street) with the newly built "L" circling the Loop. The bridge (spread above) with iron trusses, glass roof, and cast iron ornament was built without authorization the following year but was torn down immediately by authorities.

Louis Sullivan's Idea

Edited and written by Tim Samuelson; edited and designed by Chris Ware

Alphawood Foundation (distributed by University of Minnesota Press), October 2021

Hardcover | 9 x 11 inches | 384 pages | 300 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781517912796 | $45.00 | "A visual compendium revealing the philosophy and life of America’s renowned architect" (click here for publisher's description and author bios)

REFERRAL LINKS:

Alphawood Foundation (distributed by University of Minnesota Press), October 2021

Hardcover | 9 x 11 inches | 384 pages | 300 illustrations | English | ISBN: 9781517912796 | $45.00 | "A visual compendium revealing the philosophy and life of America’s renowned architect" (click here for publisher's description and author bios)

REFERRAL LINKS:

REVIEW:

While Reconstructing the Garrick is a companion to the recent Wrightwood 659 exhibition of the same name, Louis Sullivan's Idea builds upon an exhibition more than a decade old. Displayed at the Chicago Cultural Center in 2010 (check out photos of the exhibition by William Zbaren and a write-up by Lynn Becker), Louis Sullivan's Idea was curated by Tim Samuelson, the cultural historian who also wrote the text for the new book of the same name. Both books were designed by Chris Ware with traditional-looking quarter binding but different page sizes and color schemes; the complementary pair fit great on the shelf together. Louis Sullivan's Idea offers a broad overview of Sullivan's career while Reconstructing the Garrick focuses on one Adler & Sullivan building and the efforts of preservationists to save, document, and salvage it. Both are packed with visuals and a lot of informative text, making each a necessity for fans of Louis Sullivan.

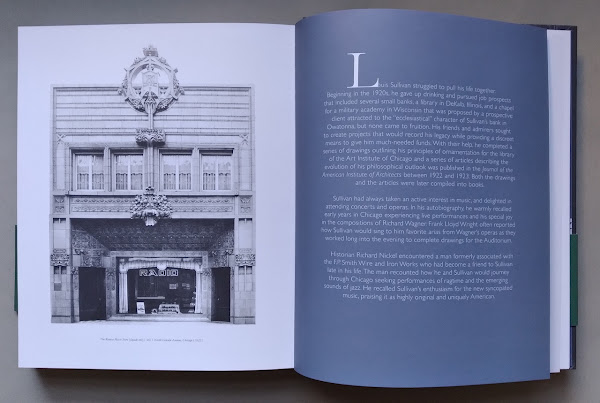

In comparing the two publications, the book on the Garrick features numerous contributors in the form of lengthy texts accompanied by relevant visuals; Louis Sullivan's Idea, on the other hand, is entirely Samuelson's voice, articulated as brief paragraphs at the start of each "chapter" of Sullivan's life, plus lengthy captions to the visuals that follow. The design by Ware features no pagination, no chapter titles, and (logically) no index. The chronological story of Sullivan's career — from his teenage years after the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 to his death in April 1924 at the age of 67 — is educational and scholarly, but these bookmaking details make it more of a scrapbook than an academic reference. It is a book to be browsed at a leisurely pace, the archival documents and images painting a portrait of Sullivan as vivid as Samuelson's words. Having grown up in suburban Chicago and long been a fan of both Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, who worked for Sullivan before making a name for himself, I know a fair amount about Sullivan and his buildings, but much of it is common knowledge gleaned from architectural histories and other secondary sources. My knowledge of Sullivan is superficial compared to Samuelson, who has had a lifelong passion for the architect and exhibits that passion in these pages. He also does not hold back any critical words, such as when he describes Sullivan's only New York building, the Bayard-Condit Building (1900; spread above), as exhibiting "a stiffness uncharacteristic of Sullivan's other work." While the reader might want to chalk up this position to NYC-Chicago rivalry, Samuelson backs it up with facts about the contractor's difficulty in getting Sullivan to sign off on mockups and how Sullivan had to work with a local architect, which compromised the quality Sullivan came to expect from well established relationships in Chicago.

The surprises in Louis Sullivan's Idea are numerous, even for people familiar with Sullivan's buildings. One standout is the pedestrian bridge Sullivan designed in 1897 to connect the Schlesinger and Mayer Department Store (this was before he was hired to expand the store on State Street) with the newly built "L" circling the Loop. The bridge (spread above) with iron trusses, glass roof, and cast iron ornament was built without authorization the following year but was torn down immediately by authorities.

Although I was not familiar with Sullivan's short-lived bridge, for a good five or six years I lived steps from Sullivan's last building commission, the facade he designed for the Krause Music Store in Chicago's Lincoln Square neighborhood. Home to the Museum of Decorative Arts (a store, not a museum) when I lived there, the facade with recessed entry and ornament projecting above the parapet is like a hyper-dense encapsulation of Sullivan's architecture. (In Chicago, I could take for granted living so close to a Sullivan, but seeing his only NYC commission in my new home means a 45-minute subway ride.) Working by himself a couple of years before his death, Sullivan did the working drawings himself; the same drawings are reprinted as a poster accompanying the book — a thrilling surprise that this Sullivan fan has already framed and hung on the wall.

FOR FURTHER READING:

FOR FURTHER READING:

- The Autobiography of an Idea by Louis H. Sullivan (Dover Publications, 2009; first published in 1924)

- Kindergarten Chats and Other Writings by Louis Sullivan (Dover Publications, 1994; first published in 1947)

- Lost Buildings by Ira Glass, Tim Samuelson and Chris Ware (WBEZ Chicago for Public Radio International, 2004)

- Louis Sullivan: Prophet of Modern Architecture by Hugh Morrison (W. W. Norton, 1998)

- Richard Nickel: Dangerous Years: What He Saw and What He Wrote by Richard Cahan and Michael Williams (CityFiles Press, 2015)

- They All Fall Down: Richard Nickel's Struggle to Save America's Architecture by Richard Cahan (Wiley, 1994)