Book Briefs #43

Here is the next installment of "Book Briefs," the series of occasional posts featuring short first-hand descriptions of some of the numerous books that publishers send to me for consideration on this blog. Obviously, these briefs are not full-blown reviews, but they are a way to share more books worthy of attention than those that end up as long reviews.

American Urbanist: How William H. Whyte's Unconventional Wisdom Reshaped Public Life by Richard K. Rein | Island Press | January 2022 | 6 x 9 inches | 352 pages | $35 | Amazon / Bookshop

The multi-faceted writer, urbanist, and sociologist William "Holly" White was known to a general audience and architects/planners, respectively, for two books: The Organization Man, a 1956 bestseller about the culture of the corporate workplace; and The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, the 1980 book that became required reading for architecture students learning how to design spaces for the way people actually use them. Richard K. Rein's enjoyable, thorough biography of Whyte tries to make sense of his subject's varied interests, which also included historic preservation and environmental conservation, and, not surprisingly, finds overlap in these two seminal books. "An effective business can learn from good public places," Rein writes. The biographer spoke with many people in the making of his book and "Holly is my hero" was a consistent refrain from them. Whyte's influence continues to this day in his numerous books, many of which remain in print, and can be seen in places such as "Holly Whyte Way" (PDF link), the unofficial name for 6-1/2 Avenue, an accidental string of POPS (Privately Owned Public Spaces) spanning six blocks in Midtown Manhattan, many of them now linked by pedestrian crosswalks. Although Whyte did not create these spaces, his research, writings, and other efforts were instrumental in improving the overall quality of POPS, helping to create places where people want to be. This biography will hopefully expand Whyte's influence on cities, workplaces, and, most importantly, the people in both of them.Building for Hope: Towards an Architecture of Belonging by Marwa al-Sabouni | Thames & Hudson | April 2021 | 6-1/2 x 9-1/2 inches | 192 pages | $29.95 | Amazon / Bookshop

While the international outcry over Russia's invasion of Ukraine is commendable in the displays of camaraderie against forceful oppression and for democratic freedoms, the response of countries, particularly in Europe and North America, reminds us that a similar outcry did not happen when Russia "intervened in Syria in 2015 to prop up the authoritarian and brutal regime of Bashar al-Assad." (These words are from an opinion piece arguing that Putin's invasion of Ukraine was enabled by the "free pass" the international community gave him in Syria.) A powerful account of living in Syria during the civil war and of finding ways to rebuild with historical continuity came from architect Marwa al-Sabouni in The Battle for Home: The Vision of a Young Architect in Syria (Thames & Hudson, 2016). Her followup to that popular memoir is Building for Hope, billed as an exploration of "how buildings and cities might be rebuilt in the aftermath of conflict, crisis or financial depression." In a review I edited at World-Architects and I recommend readers check out, Madeline Carey describes it as "an ambitious treatise that combines stories from daily life in Syria with observations of cities such as Detroit, Helsinki, Bristol, Beirut, Dubai, and Amsterdam" and finds it "expansive, abstract, and at times extraordinarily idealistic" as well as "dense and daring." Like The Battle for Home, Building for Hope's text is accompanied by the architect's own sketches, this time depicting places well beyond her native Syria.

While the international outcry over Russia's invasion of Ukraine is commendable in the displays of camaraderie against forceful oppression and for democratic freedoms, the response of countries, particularly in Europe and North America, reminds us that a similar outcry did not happen when Russia "intervened in Syria in 2015 to prop up the authoritarian and brutal regime of Bashar al-Assad." (These words are from an opinion piece arguing that Putin's invasion of Ukraine was enabled by the "free pass" the international community gave him in Syria.) A powerful account of living in Syria during the civil war and of finding ways to rebuild with historical continuity came from architect Marwa al-Sabouni in The Battle for Home: The Vision of a Young Architect in Syria (Thames & Hudson, 2016). Her followup to that popular memoir is Building for Hope, billed as an exploration of "how buildings and cities might be rebuilt in the aftermath of conflict, crisis or financial depression." In a review I edited at World-Architects and I recommend readers check out, Madeline Carey describes it as "an ambitious treatise that combines stories from daily life in Syria with observations of cities such as Detroit, Helsinki, Bristol, Beirut, Dubai, and Amsterdam" and finds it "expansive, abstract, and at times extraordinarily idealistic" as well as "dense and daring." Like The Battle for Home, Building for Hope's text is accompanied by the architect's own sketches, this time depicting places well beyond her native Syria.

Golconde: The Introduction of Modernism in India by Pankaj Vir Gupta, Christine Mueller, Cyrus Samii | Actar Publishers / Vir.Mueller Architects | December 2021 (Second edition) | 8 x 9 inches | 112 pages | $29.95 | Amazon / Bookshop

Although, as the name clearly says, my 2016 book 100 Years, 100 Buildings features 100 buildings, the number that I considered and listed in the back of the book is hundreds more. One of them is Golconde, the dormitory in Pondicherry, India, designed by Antonin Raymond for the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, founded by yoga practitioner Sri Aurobindo and handed down to Mirra Alfassa, aka "The Mother," in 1926. Dates on the building's completion vary by source, with research on my book determining 1945, volume eight of World Architecture 1900-2000: A Critical Mosaic bumping it to 1948, and the authors of Golconde: The Introduction of Modernism in India, first published in 2010, indicating a substantial completion date of 1942. (The same authors, Pankaj Vir Gupta and Christine Mueller of Vir.Mueller Architects, wrote at Architectural Digest last year that it was completed in 1945.) While the exact completion date of the building is ambiguous, it's clear that Raymond started the project in 1936, when he was still living and working in Tokyo, and continued it after his departure from Japan in 1937. He spent some months in Pondicherry before returning to the United States, but not as long as George Nakashima, who spent three years living at the Ashram to carry out the dormitory project. Nakashima's involvement is one of many things I learned in the short but necessary book on an important work of modern architecture. Coincidentally, the Nakashima Foundation for Peace in New Hope, Pennsylvania, is opening the exhibition Golconde, The Introduction of Modernism in India with a reception on June 12, after which it is open to the public "on select Saturdays" until October.

Greta Magnusson Grossman: Modern Design from Sweden to California by Harriet Harriss, Naomi House | Lund Humphries | February 2022 | 7-1/2 x 10 inches | 144 pages | $59.99 | Amazon / Bookshop

Unlike many of her peers in architecture, interior design, and furniture design in the middle of the last century, Greta Magnusson Grossman is not a household name. I'll admit I did not know of her before getting this book in the mail from Lund Humphries. This neglect can be attributed greatly to a context that privileged men over women and architects over multi-disciplinary designers. As such, Magnusson Grossman is one of many women whose work is little known today but should be better known, for no other reason than the sheer quality of it. I'm particularly taken by the Cobra table lamp and Grasshopper floor lamp, both produced by Ralph O. Smith and both her best known designs. But the houses she designed in California, some of them anticipating qualities of later, better known houses by Pierre Koenig and others, are also exceptional. Given the complicated nature of telling a history of a designer whose image was crafted by people working against her, in some ways, this book devoted to Magnusson Grossman isn't a straightforward monograph. As the authors put it in their introduction, the book strikes a balance between a "'tentative' methodology for feminist historical restitution and a selective catalogue of the work itself." (An adapted excerpt of the book can be read at Places Journal.)

Unlike many of her peers in architecture, interior design, and furniture design in the middle of the last century, Greta Magnusson Grossman is not a household name. I'll admit I did not know of her before getting this book in the mail from Lund Humphries. This neglect can be attributed greatly to a context that privileged men over women and architects over multi-disciplinary designers. As such, Magnusson Grossman is one of many women whose work is little known today but should be better known, for no other reason than the sheer quality of it. I'm particularly taken by the Cobra table lamp and Grasshopper floor lamp, both produced by Ralph O. Smith and both her best known designs. But the houses she designed in California, some of them anticipating qualities of later, better known houses by Pierre Koenig and others, are also exceptional. Given the complicated nature of telling a history of a designer whose image was crafted by people working against her, in some ways, this book devoted to Magnusson Grossman isn't a straightforward monograph. As the authors put it in their introduction, the book strikes a balance between a "'tentative' methodology for feminist historical restitution and a selective catalogue of the work itself." (An adapted excerpt of the book can be read at Places Journal.)

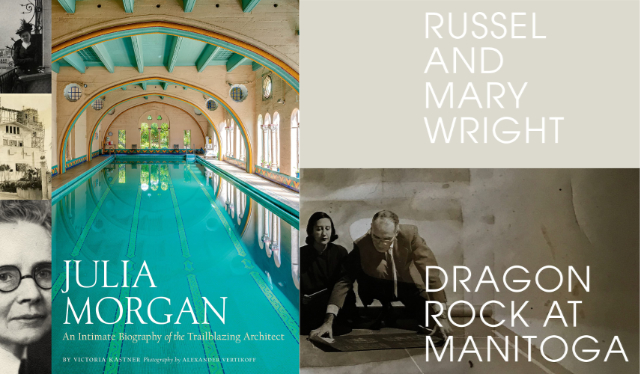

Julia Morgan: An Intimate Biography of the Trailblazing Architect by Victoria Kastner | Chronicle Books | March 2022 | 8-1/2 x 10-1/4 inches | 240 pages | $32.50 | Amazon / Bookshop

On my first and so far only visit to the Bay Area, which took place about 25 years ago, a planned excursion to Napa Valley was derailed by — no joke — an earthquake with its epicenter there. Instead of catching a peek of Herzog & de Meuron's Dominus Winery, my friends and I drove to Oakland, to see the most memorable work of architecture of my stay: the Chapel of the Chimes, a columbarium designed by Julia Morgan in the 1920s. So when Morgan was named the 2014 recipient of the AIA Gold Medal, more than 50 years after her death, I thought of Chapel of the Chimes rather than Hearst Castle, the considerably more famous estate she designed for William Randolph Hearst over the course of 30 years. The Chapel of the Chimes makes a brief appearance in Victoria Kastner's well-researched and well-received biography of Julia Morgan, as do a number of some of the roughly 700 projects undertaken by Morgan, but Hearst Castle is the thread the runs through the whole book, echoing the way it absorbed so much of the California architect's adult life. People who know Morgan solely for San Simeon will be pleased with Kastner's biography of Morgan, though they'll also learn about the smaller projects that deserve as much attention as the biggest and most famous of them all.

Russel and Mary Wright: Dragon Rock at Manitoga by Jennifer Golub | Princeton Architectural Press | December 2021 | 11 x 10 inches | 208 pages | $60 | Amazon / Bookshop

I'm writing these words over Memorial Day weekend, the traditional, unofficial start of summer in the United States, when millions of Americans hit the road or fly to summery destinations. While I'm at home this weekend, the thought of taking day trips or weekend trips close to home is provoked by the weather warming up, this holiday weekend rolling around once again, and two years of very little travel. Flipping through Dragon Rock at Manitoga is adding to the itch, bumping up a place long on my to-go list to near the top. Manitoga is "the former home and 75-acre woodland garden of American industrial designer Russel Wright (1904–1976)," located in Garrison, New York, a 90-minute train ride north of New York City. The name "Dragon Rock" refers to the house and studio he developed with architect David Leavitt (1918–2013), as well as the site's quarry landscape. Wright's wife and partner in their design practice, Mary (née Einstein, 1904–1952), did not live long enough to see Manitoga take shape, though she helped conceive Dragon Rock and therefore shares equal billing in this lavishly illustrated monograph by Jennifer Golub that is as much about their life and practice as it is about the home and studio. The book's many photographs and drawings of the wares they designed together, and of Dragon Rock in its beautiful Hudson River setting, are what make a firsthand experience of Manitoga so tempting — and necessary.

I'm writing these words over Memorial Day weekend, the traditional, unofficial start of summer in the United States, when millions of Americans hit the road or fly to summery destinations. While I'm at home this weekend, the thought of taking day trips or weekend trips close to home is provoked by the weather warming up, this holiday weekend rolling around once again, and two years of very little travel. Flipping through Dragon Rock at Manitoga is adding to the itch, bumping up a place long on my to-go list to near the top. Manitoga is "the former home and 75-acre woodland garden of American industrial designer Russel Wright (1904–1976)," located in Garrison, New York, a 90-minute train ride north of New York City. The name "Dragon Rock" refers to the house and studio he developed with architect David Leavitt (1918–2013), as well as the site's quarry landscape. Wright's wife and partner in their design practice, Mary (née Einstein, 1904–1952), did not live long enough to see Manitoga take shape, though she helped conceive Dragon Rock and therefore shares equal billing in this lavishly illustrated monograph by Jennifer Golub that is as much about their life and practice as it is about the home and studio. The book's many photographs and drawings of the wares they designed together, and of Dragon Rock in its beautiful Hudson River setting, are what make a firsthand experience of Manitoga so tempting — and necessary.