Architectural Exhibitions and Their Books

Preparing for this post I counted roughly one hundred books in my library that are related to exhibitions. Surprisingly, given that I tend to buy catalogs and other companion books to exhibitions I visit, only a quarter of those hundred are exhibitions I have seen in person. Granted, a fair number of them are classics that predate my existence, such as The International Style, the book version of MoMA's Modern Architecture: International Exhibition from 1932, or are from exhibitions that happened on the other side of the world, including two of the exhibition catalogs featured here. The fact I have so many catalogs that do not function as souvenirs to exhibitions I visited points to their enduring value: They are permanent records of temporary displays and, as such, expose the research and contents from exhibitions to considerably more people than who attended.

Not all books coming out of architectural exhibitions are the same. Many of them function like art catalogs and have a two-part structure of critical essays followed by color plates that catalog the works on display. Such a normative structure works for monographic shows and historical surveys, both of which consist primarily of previously made content that can be documented ahead of time for publication. But many architectural exhibitions, especially the ubiquitous biennials and triennials, feature projects that are specially commissioned and are often installed right up until opening day (architects and their deadlines!). Such timelines make it hard for a companion book to be released alongside an exhibition. Therefore, many books on architectural exhibitions show preliminary images for the projects, a tactic that prioritizes attendance, when visitors can also see final models, drawings, photographs, and so forth.

For these and other reasons, books on architectural exhibitions often depart from catalogs and instead serve as extensions of the displays, offering other layers of information rather than repackaging the contents of the exhibitions. The critical essays in typical catalogs offer such a layer, since they invite scholars to dig into the subject of an exhibition and present their essays in a place where people can sit and focus on the words (too much wall text in an exhibition is never a good thing), but some catalogs go much further. I'm thinking of Bard Graduate Center's Eileen Gray, beautifully designed by Irma Boom and full of essays and documentation of Gray's projects, with the latter showing sides and movements of furniture that could not be seen in the exhibition. (The exhibition being cut severely short by the pandemic made that catalog much more valuable.)

There are many other examples in the vein of Eileen Gray, including: the three-volume OfficeUS companion to the US Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale; Rem Koolhaas's gargantuan Elements of Architecture, documenting one component of the main exhibition at the Venice Biennale, also in 2014 and also designed by Irma Boom; and OMA's Palermo Atlas, a preparatory research publication for Manifesta 12, curated by former OMA partner Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli. Although these and other such books would not exist without the exhibitions they're related to, they exploit the innate qualities of books to offer content that makes them work by themselves as well. These types of exhibition books are my favorites, whether I managed to see the exhibitions or not.

- Futures of the Architectural Exhibition: Mario Ballesteros, Giovanna Borasi, Ann Lui, Ana Miljacki, Zoë Ryan, Martino Stierli, Shirley Surya in Conversation with Students edited by Reto Geiser and Michael Kubo, published by Park Books, 2023 (Amazon / Bookshop)

- Another Breach in the Wall: The City as a Common Good by Davide Tommaso Ferrando and Daniel Tudor Munteanu, published by Solitude Project, 2022 (Purchase at PUNCH Bookshop)

- Lacaton & Vassal: Espacio libre, transformación, habiter / Free space, transformation, habiter published by Fundación ICO / Puente Editores, 2021 (Amazon / Bookshop)

The book that has me thinking about exhibitions and their books is Futures of the Architectural Exhibition, which features interviews with seven primarily North American curators, conducted between 2018 and 2021 in concert with lectures and student workshops at Rice University, where editors Reto Geiser and Michael Kubo teach. Although the conversations tackle considerations of exhibitions that are well beyond books — including acquisitions and archives, digital media, authors and audiences, and the diversity of subjects, among other things — the parts of the conversations addressing books held my attention the most. Before delving into some highlights of the book in this regard, the format of the book reminds me of Léa-Catherine Szacka's Biennials/Triennials: Conversations on the Geography of Itinerant Display (GSAPP, 2019); with their interviews focused on various types of architectural exhibitions and venues, the two books definitely make good companions. Readers interested in architectural exhibitions more generally should also check out Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen's Exhibit A: Exhibitions That Transformed Architecture, 1948–2000 (Phaidon, 2018). And although I haven't seen these in person, Fleur Watson's The New Curator: Exhibiting Architecture and Design (Routledge, 2021) and Zoë Ryan's As Seen: Exhibitions that Made Architecture and Design History (AIC, 2017) are highly relevant titles that seem like they should be of interest to the same readers.

The first interview in Futures happens to be with Ryan, who was curator of architecture and design at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) at the time of the interview but is now director of the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania. As Seen is one of the topics the students talk about with Ryan, from its start as a component of The Future Is Not What It Used To Be, the Istanbul Design Biennale she curated in 2014, to its display at AIC one year later and its publication by the museum one year after that. The exhibition(s) and book definitely make Ryan an expert on exhibitions and their books. Here's a choice quote, related to some of my words above: "Books are such a privilege to work on. I say 'books' specifically because I'm not really interested in creating exhibition catalogs as such. The book should be its own thing. It's an opportunity to build on the content of the show and reflect on it." The Rice students pick up on that distinction, pointing out that the famous The International Style book was not the catalog to the MoMA exhibition; the actual catalog is not so well known and is quite rare (luckily, it is available for download as a PDF), but it is valuable for including the "Housing" section that was contributed by Lewis Mumford but was omitted from the polemical and style-focused book by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock. Ryan replies with another example: the atypical catalog for This Is Tomorrow, held at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1956. Ryan says "it was envisioned as a guidebook [...] that you bought before seeing the exhibition and then used as a guide to learn about the installations." With its small size (6.5" square) and spiral binding, the book is "an object in its own right." She concludes: "I strive to create these kinds of books." (That catalog, long sought after and hard to find, was reprinted by the gallery in a facsimile edition in 2010.)

Very much "an object in its own right" is the catalog to Another Breach in the Wall, the main exhibition of the Beta 2022 Timișoara Architecture Biennial, curated by Daniel Tudor Munteanu and Davide Tommaso Ferrando. Paralleling the way the exhibition held last fall situated many of its contributions in Timișoara's "Monkey House" and even more of them on a "Trail" looping its way around the historical center of the Romanian city, the catalog is split into two books: two exposed-binding paperbacks set into a paperback wrapper that doubles as a map for the Trail and a floor plan of the Monkey House. Therefore, like the 1956 Whitechapel Gallery exhibition that the Beta curators may or may not have known about, the two-volume catalog acted as a guide for visitors: The various projects are keyed to the map and plan with three-letter designations and are ordered in the bound volumes according to a designated route through the city Trail and the Monkey House building. This is one of those books in my library that relates to an exhibition I didn't attend, so I can't say how effectively it worked as a guide, but — with its sheet of stamps designed by De Facto (Jorie Horsthuis and Floor Koomen) and elastic strap holding the various parts together — it sits proudly on my shelf next to my facsimile reprint of This Is Tomorrow.

|

| The various parts of Another Breach in the Wall (Romanian version) |

So what does "Another Breach in the Wall" mean, and what were the projects on display? Though humorously referencing a Pink Floyd song, the name pertains to "the loopholes by means of which breaches are opened through [...] walls, making new and unexpected paths possible." ("Loopholes" would have been an accurate title though not colorful enough, I gather.) So the curators assembled "projects and actions that are capable of generating exceptional urban spaces by questioning the laws, rules, and codes according to which cities are produced and inhabited." That questioning extends to the tactics of the exhibition: close to twenty commissioned works, many of them taking the form of "micronations," accompanied by dozens and dozens more "replicas," "unauthorized replicas," "elaborations," and "unauthorized elaborations." The projects are diverse, to say the least: Pussy Riot, Jill Magid's The Proposal, Chinese Nail Houses, Michael Rakowitz's paraSITE... The book for the last, Circumventions, is described with the words "to get around the rules, to find loopholes, to initiate idiosyncratic solutions, to employ subtle metaphor to highlight problematic situations" and appears to supply a definition for the curators. Beyond serving as a guide, the two-volume Breach book is also a survey of "other ways of doing architecture" and as such echoes — and, in an essence, updates — the great twelve-year-old book Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture.

Returning to Futures of the Architectural Exhibition, another interview worth discussing here in terms of the relationship between architectural exhibitions and their books is the one with Martino Stierli, who has been chief architecture and design curator at MoMA since 2015. The exhibitions he has organized there include, in chronological order (links point to my write-ups on World-Architects): Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980 and The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985, both major exhibitions with lavish, scholarly catalogs; Reuse, Renew, Recycle: Recent Architecture from China, a small exhibition in the museum's free ground-floor storefront gallery; and the current exhibition, New York, New Publics, the first installment of the "Architecture Now" series. Conducting the interview in fall 2018, when Toward a Concrete Utopia was on display, the students ask Stierli: "Could you elaborate on how the book and the exhibition are different, or on how these are complementary?" He replies that, in an exhibition, "you want to reduce your argument to a limited number of stringent points supported by visual material to bring across the message," but "the book is the better medium to discuss [...] theoretical perspectives." This visual/textual dichotomy of exhibition/book means Stierli's catalogs "not only include essays by the curators but also give space to the voices of the leading scholars in a given field."

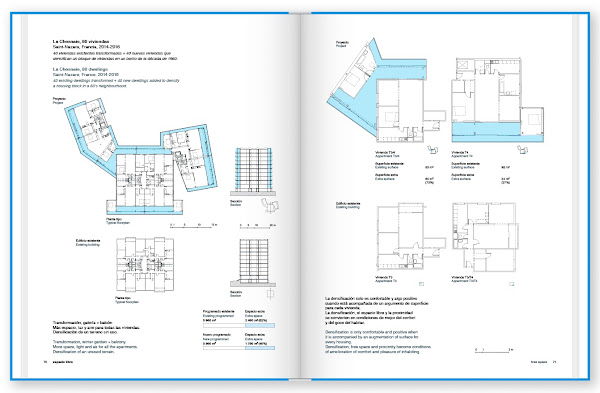

Stierli's approach is not unique, but it is very much rooted in him being an architectural historian. Other exhibitions at other venues organized by other curators with other backgrounds would lead, naturally, to catalogs taking different shapes. Another recent exhibition I didn't see in person, but whose catalog I also like is Lacaton & Vassal: Espacio libre, transformación, habiter, which opened at Museo ICO in Madrid in October 2021, the same year the French architects won the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The catalog, published by Fundación ICO and Puente Editores, has a three-part structure that parallels the intertwining themes of the exhibition, which in turn expresses the themes found in the buildings designed by Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal: free space, transformation, and habiter. The last, referring to how people live in spaces designed with freedom and flexibility in mind, is illustrated with stills from a 2019 film commissioned by FRAC, one of their clients. The second basically functions as a visual catalog of their projects between 1986 to 2020, a selection that conveys their attitude, made famous by the Pritzker win, to "never demolish, never subtract or replaces, always add, transform [...] start off with the existing to do more and to do better." But the first section is the most appealing part of the book, with "free space" — defined, in part, by the architects as "space that isn't asked for, but that we find indispensable" — illustrated through shaded floor plans and building sections of numerous projects, many of them the housing transformations Lacaton & Vassal are known for:

Prefacing the three parts of the book is an interview with Lacaton and Vassal conducted by Enrique Walker in June 2021, three months after they were named the Pritzker laureates. Walker focuses the duo's attention on their work at Palais de Tokyo, the 1937 building in Paris that has been used for temporary exhibitions of contemporary art since 2002 (they intervened in two phases, starting in 2002 and 2012). To Walker, "Palais de Tokyo cuts across the three notions around which you organize this exhibition [at Museo ICO ...], namely: starting from the existing conditions, building the maximum space, and offering possibilities for use and making the space one's own." The choice of project is fitting since, of all the projects illustrated in the first section of the book, Palais de Tokyo is the only one whose data indicates a 100% supply of "free space." Lacaton told Walker: "From the very beginning, we thought that we would not partition the space, or constrain it, but rather leave it open, like this square in Marrakesh," referring to Jemaa el-Fnaa, a source of inspiration for the architects. As such, the whole Palais de Tokyo is open, free to be used by the curators however they choose.

If the small book of interviews carried out by the students of Reto Geiser and Michael Kubo tackles, as the name indicates, the future of architectural exhibitions, what is the future of their books? To grab one more relevant quote from the book, Giovanna Borasi, now director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal, says that, instead of shifting to digital publications (after some of them, the CCA's "digital output" has shifted to podcasts and movies), "we have thematic books, manifesto books, and more archival books," in which "each type of book has its own format." One could interpret these words to mean curators and editors, and museums and other institutions no longer need to envision companion books to architectural exhibitions as catalogs or other normative formats. They should find ways to take the research, scholarship, and imagery from an exhibition and apply it to a book that exploits the possibilities of the medium. This has been done many times in the past and is certainly being done today — as Another Breach in the Wall, in particular here, attests — but for such books to remain relevant they must push the boundaries on what it means to exhibit architecture in the pages of a book.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated for spam.